[from

Jemima Sissons @

The Wall Street Journal, 3 June 2011]

[a big thank you to Joe Meuth for this post]

Barbecuing the Perfect SteakAs Chef Fernando Trocca Prepares the Asado, He Explains Why Argentinian Beef Is the Best in the World"Never, ever cook with flames—this is probably the most important thing to learn. Flames are the American way."

|

Chef Fernando Trocca gives writer Jemima Sissons

a lesson on the Argentinean way of barbecuing. |

Fernando Trocca, one of Argentina's most esteemed chefs, is sharing this piece of advice while showing me his pride and joy: an almighty black cast-iron parrilla, or Argentinean barbecue grill, that is the centerpiece of his fine dining restaurant

Sucre. He is instructing me in the Argentinean way of barbecuing. To the right is a large pit, filled with the smoky aroma of quebracho (a red hardwood), which has been slowly turning into embers for the past hour-and-a-half.

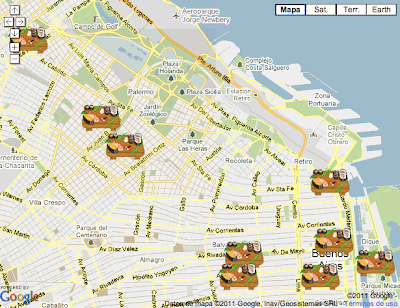

As well as owning Sucre, located in a shabby-chic area of northern Buenos Aires, Mr. Trocca is executive chef of the Argentinean restaurant group

Gaucho Grill, with branches across the U.K. and one in Beirut.

Asado—both the name of a barbecue as a social event, and a cut of beef (short ribs)—was part of the chef's weekly life, growing up in Buenos Aires.

|

| preparing the meat |

"Asado is a ritual—it is about people cooking together," explains Mr. Trocca. "They mostly happen on a Saturday or Sunday. We don't plan anything here. They usually happen spontaneously. If you have outdoor space, you have a parrilla."

The main difference between an Argentinean grill and a European one is that in the Argentinean grill the fire is on one side of the pit at the bottom. As the embers become red hot, they are pushed to the other side. The meat is placed over these only, hence the first cardinal rule of grilling in Argentina: Never over an open flame.

Mr. Trocca, 45 years old, loved cooking from an early age. "I used to have a grandmother who was a great chef. The passion comes from there," he says.

In 1985, he started his training in Buenos Aires. Five years later he packed his bags for Europe, where his training included a stint with the legendary

Massimo Bottura of Osteria Francescana in Modena, Italy. After moving to New York, where he worked at fashionable culinary hot spot Vandam, he returned in 2001 to open Sucre, which mixes typical asado with modern and European dishes such as octopus carpaccio and whitefish confit with arugula. He has been executive chef at Gaucho Grill for the past three years.

|

| the completed dish |

The asado derives from the Spanish

asar, to roast, and originated as a gaucho [South American cowboy] ritual. There are still differences with the types of grill found in Mr. Trocca's restaurant and garden, and the ones the gauchos use. Some gauchos still cook in a croce form—whole lambs, for example, are strung up on a cross and cooked slowly next to a fire in the middle. However, in reality, "most gauchos use gas nowadays," Mr. Trocca says. They also prefer their meat to be extremely well done, he says, and this is how it still comes in many Argentine restaurants unless otherwise requested.

The asado starts an hour-and-a-half before eating is to begin, when the fire is lit. Mr. Trocca uses wood only. "Everything is a ceremony," Mr. Trocca says. "I always start by opening a bottle of wine, probably a Torrontes [a white grape from Argentina]. I start with the fire, hand around some salami. First up are the sausages, blood sausage, and chorizo—these are much more fatty than in Europe. Then comes the offal—sweetbreads, kidneys and chinchulines [intestines]—with lots of lemon juice. Only then comes the beef, lamb and pork, often two to three hours into the meal."

Mr. Trocca starts the lesson by showing me how to make

chimichurri sauce, a mixture of flat-leaf parsley, garlic, onions, red pepper, dried sweet chili, olive oil and vinegar. He also makes a fresh criollo salsa: simply tomatoes without the seeds, onion and lashings of Argentinean olive oil. In a traditional asado, these are often the only accompaniments to the meat—perhaps with some sweet potatoes that have been baked in foil with olive oil in the fire for 20 minutes, and then slathered in butter.

However, the main event is the meat, and Argentinean steak has the reputation for being some of the best, if not the best, in the world. When asked why, Mr. Trocca explains it is all about geography: "The cows live in the pampas (grasslands), where all they eat is amazing grass. They just walk around, there is no stress and there are no hills, so they have no muscles. It all comes down to diet and muscles." He says that in Europe, he would use Aberdeen Angus, as the closest equivalent.

Mr. Trocca starts to grill a five-centimeter, finely marbled rib-eye on the parrilla, which will take 12-15 minutes in total to be pink in the middle. A good indicator of when to turn it over is when the blood rises to the surface of the raw side. He elaborates on which cuts of beef he favors: asado (short rib), followed by rib-eye and skirt steak. Fillet doesn't stand a chance: "In 10 years in Sucre, I have never had it on the menu, there is no taste as there is no fat. I know how popular fillet is. If it is on the menu, it will sell. I like to re-educate people a bit about different cuts."

One of the most delicious things on the menu, and rarely seen on the barbecues or restaurant menus of Europe, is

matambre de cerdo: pork flank steak. After being salted first (no pepper, as with all the meat), it is cooked on the grill for four minutes on either side and served with potato salad.

And what would he never put on a barbecue? "Chicken, unless it is

spatchcocked, and fish, which simply doesn't work well."

What does work well, however, is grilled provolone cheese. This is a nod to Argentina's multicultural history, as much of the country's cuisine has Spanish and Italian influences. Here, provolone cheese is simply cut into four-centimeter discs, and left to dry out for a few days, before being grilled for two minutes either side. This is served with chimichurri sauce.

As Mr. Trocca painstakingly layers discs of potato onto a pan—to be served as a sort of potato doily with the beautifully tender rib eye—he explains what he loves most about asado: "It is the most social of all cooking, and, gastronomically, it is what Argentina is most famous for," he says. "There is nothing like a slow asado, all your friends sitting around and talking; I will send out things little by little for them to enjoy. Sometimes it goes on for four hours or longer—to me that is the perfect meal."