The guinea pig plays an important role in the folk culture of many Indigenous South American groups, especially as a food source, but also in folk medicine and in community religious ceremonies. Since the 1960s, efforts have been made to increase consumption of the animal outside South America.

|

| cuy being raised at home in Andean fashion |

The scientific name of the common species is Cavia porcellus, with porcellus being Latin for "little pig". Cavia is New Latin; it is derived from cabiai, the animal's name in the language of the Galibi tribes once native to French Guiana. Cabiai may be an adaptation of the Portuguese çavia (now savia), which is itself derived from the Tupi word saujá, meaning rat. Guinea pigs are called quwi or jaca in Quechua and cuy or cuyo (pl. cuyes, cuyos) in the Spanish of Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia. Ironically, breeders tend to use the more formal "cavy" to describe the animal, while in scientific and laboratory contexts it is far more commonly referred to by the more colloquial "guinea pig".

|

| Moche guinea pig |

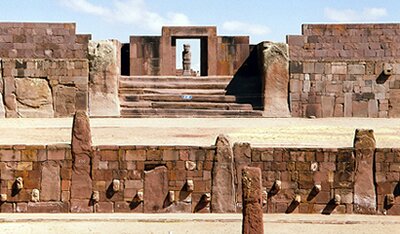

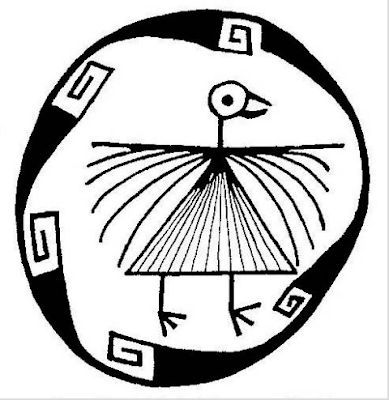

The common guinea pig was first domesticated as early as 5000 BC for food by tribes in the Andean region of South America (present-day the southern part of Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia), some thousands of years after the domestication of the South American camelids. Statues dating from ca. 500 BC to 500 AD that depict guinea pigs have been unearthed in archaeological digs in Peru and Ecuador. The Moche people of ancient Peru worshipped animals and often depicted the guinea pig in their art. From ca. 1200 AD to the Spanish conquest in 1532, selective breeding resulted in many varieties of domestic guinea pigs, which form the basis for some of the modern domestic breeds. They continue to be a food source in the region; many households in the Andean highlands raise the animal, which subsists off the family's vegetable scraps. Folklore traditions involving guinea pigs are numerous; they are exchanged as gifts, used in customary social and religious ceremonies, and frequently referenced in spoken metaphors. They also play a role in traditional healing rituals by folk doctors, or curanderos, who use the animals to diagnose diseases such as jaundice, rheumatism, arthritis, and typhus. They are rubbed against the bodies of the sick, and are seen as a supernatural medium. Black guinea pigs are considered especially useful for diagnoses. The animal also may be cut open and its entrails examined to determine whether the cure was effective. These methods are widely accepted in many parts of the Andes, where Western medicine is either unavailable or distrusted.

|

| cuy asado |

Guinea pig meat is high in protein and low in fat and cholesterol, and is described as being similar to rabbit and the dark meat of chicken. The animal may be served fried (chactado or frito), broiled (asado), or roasted (al horno), and in urban restaurants may also be served in a casserole or a fricassee. Ecuadorians commonly consume sopa or locro de cuy, a soup dish. Pachamanca or huatia, a process similar to barbecueing, is also popular, and is usually served with corn beer (chicha) in traditional settings.