[Rudi Goldman's latest video]

The New York Times touted TORRONTÉS as "the hottest thing to arrive from Argentina since the tango . . . some say it will be as popular in the United States as pinot grigio." Discover Torrontes explores this little known treasure of a wine and Cafayate, Argentina's ideal conditions for growing the finest Torrontes grapes in the world.

Cafayate's altitude, winds and water creates grapes with distinctive floral aromas, producing the finest Torrontes wines from Argentina.

Discover Torrontes features activities surrounding the 2011 Torrontes harvest at La Estancia de Cafayate, in Salta province, Argentina.

Showing posts with label wine. Show all posts

Showing posts with label wine. Show all posts

Wednesday, June 8, 2011

Monday, April 18, 2011

Malbec!

[from Fred Tasker @ Miami Herald, 15 April 2011]

Malbec becomes Argentina’s flagship red wine

I wish to report, modestly, that I wrote a wine column in May 1997 that started like this:

“You read it here first: Malbec, given time, will be the finest wine to come from Argentina. It will put that country’s arid, isolated wine country on the world map.”

Today I submit that it has happened, in spades.

Malbec came to Miami first because of our cultural connections to South America. Today it’s all over the wine world, by far Argentina’s most popular export wine. And amazingly, you will find tasting notes here for two malbecs that still cost only $6 each.

What we’ve learned since 1997 is that malbec is malleable. It can be turned into a pretty good $6 wine – nothing you’d cellar for decades, but a rich, fruity, user-friendly everyday wine. And it can be turned into a $55 stunner that’s little short of majestic.

Centuries ago, malbec was a minor grape used along with cabernet sauvignon, merlot, petit verdot and cabernet in the blending of France’s vaunted Bordeaux reds. It was inky black and hard as nails in France’s maritime climate, and was used to add color and structure to the wines.

In Argentina, on the sunny eastern slopes of the Andes around Mendoza with their hot days and cold nights, high altitudes, near total lack of rainfall and poor soils, malbec was transformed.

In a blind tasting, I would identify it as tasting just like those Brach’s candies: black cherries and dark chocolate, sweet, rich and creamy.

At Trapiche, Argentina’s biggest winery with 2,500 acres divided into dozens of vineyards under dozens of growers, all malbec winemaking is concentrated under a single winemaker, Daniel Pi.

Each year Trapiche chooses three of its top growers and bottles their wines exclusively for distribution. One of them this year is the “Icons” single-vineyard malbec by grower Adolfo Ahumada, from 3,000 feet up the Andes at Valle de Uco.

Another top winery, Michel Torino Estate, makes malbec with organic grapes, fertilizing with sheep manure (Aren’t you glad to know?), cutting weeds with machetes, adding less sulfur as a preservative in the final produce.

So enjoy. Just don’t tell the Argentines how good their wines are. I’m afraid they’ll jack up their prices.

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

• 2010 Michel Torino Malbec, Cafayate Valley, Argentina: black cherry and dark chocolate flavors, full-bodied, big, ripe tannins; $13.

• 2007 Trapiche “Icons” Malbec Single Vineyard Vina Adolfo Ahumada, Mendoza, Argentina: aromas of cedar and smoke, concentrated mulberry and mocha flavors, big, ripe tannins, smooth, long finish; $55.

RECOMMENDED

• 2008 Trapiche Broquel Malbec, Mendoza: soft and rich, with flavors of black plums and mocha, ripe tannins, very smooth; $15.

• 2009 Falling Star Malbec, Cuyo, Argentina: soft, sweet and ripe, with black plum and cinnamon flavors; $6.

• 2010 Astica Malbec, Cuyo, Argentina: soft and sweet, with black cherry and milk chocolate flavors; $6.

• 2009 Trapiche Malbec, Mendoza, Argentina: black cherry and coffee flavors, big, ripe tannins, very smooth; $7.

• 2008 Michel Toreno Malbec “Don David” Malbec, Cafayate Valley, Argentina: hint of oak, flavors of black currants and coffee, with firm tannins; $16.

• 2010 Michel Torino Estate “Cuma” Malbec, Cafayate Valley, Argentina: flavors of black plums and prunes and cinnamon, rich and soft; $13.

• 2008 Trapiche Oak Cask Malbec, Mendoza, Argentina: hint of vanilla from oak aging, flavors of black cherries and black pepper, concentrated; $10.

Malbec becomes Argentina’s flagship red wine

I wish to report, modestly, that I wrote a wine column in May 1997 that started like this:

“You read it here first: Malbec, given time, will be the finest wine to come from Argentina. It will put that country’s arid, isolated wine country on the world map.”

Today I submit that it has happened, in spades.

Malbec came to Miami first because of our cultural connections to South America. Today it’s all over the wine world, by far Argentina’s most popular export wine. And amazingly, you will find tasting notes here for two malbecs that still cost only $6 each.

What we’ve learned since 1997 is that malbec is malleable. It can be turned into a pretty good $6 wine – nothing you’d cellar for decades, but a rich, fruity, user-friendly everyday wine. And it can be turned into a $55 stunner that’s little short of majestic.

Centuries ago, malbec was a minor grape used along with cabernet sauvignon, merlot, petit verdot and cabernet in the blending of France’s vaunted Bordeaux reds. It was inky black and hard as nails in France’s maritime climate, and was used to add color and structure to the wines.

In Argentina, on the sunny eastern slopes of the Andes around Mendoza with their hot days and cold nights, high altitudes, near total lack of rainfall and poor soils, malbec was transformed.

In a blind tasting, I would identify it as tasting just like those Brach’s candies: black cherries and dark chocolate, sweet, rich and creamy.

At Trapiche, Argentina’s biggest winery with 2,500 acres divided into dozens of vineyards under dozens of growers, all malbec winemaking is concentrated under a single winemaker, Daniel Pi.

Each year Trapiche chooses three of its top growers and bottles their wines exclusively for distribution. One of them this year is the “Icons” single-vineyard malbec by grower Adolfo Ahumada, from 3,000 feet up the Andes at Valle de Uco.

Another top winery, Michel Torino Estate, makes malbec with organic grapes, fertilizing with sheep manure (Aren’t you glad to know?), cutting weeds with machetes, adding less sulfur as a preservative in the final produce.

So enjoy. Just don’t tell the Argentines how good their wines are. I’m afraid they’ll jack up their prices.

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

• 2010 Michel Torino Malbec, Cafayate Valley, Argentina: black cherry and dark chocolate flavors, full-bodied, big, ripe tannins; $13.

• 2007 Trapiche “Icons” Malbec Single Vineyard Vina Adolfo Ahumada, Mendoza, Argentina: aromas of cedar and smoke, concentrated mulberry and mocha flavors, big, ripe tannins, smooth, long finish; $55.

RECOMMENDED

• 2008 Trapiche Broquel Malbec, Mendoza: soft and rich, with flavors of black plums and mocha, ripe tannins, very smooth; $15.

• 2009 Falling Star Malbec, Cuyo, Argentina: soft, sweet and ripe, with black plum and cinnamon flavors; $6.

• 2010 Astica Malbec, Cuyo, Argentina: soft and sweet, with black cherry and milk chocolate flavors; $6.

• 2009 Trapiche Malbec, Mendoza, Argentina: black cherry and coffee flavors, big, ripe tannins, very smooth; $7.

• 2008 Michel Toreno Malbec “Don David” Malbec, Cafayate Valley, Argentina: hint of oak, flavors of black currants and coffee, with firm tannins; $16.

• 2010 Michel Torino Estate “Cuma” Malbec, Cafayate Valley, Argentina: flavors of black plums and prunes and cinnamon, rich and soft; $13.

• 2008 Trapiche Oak Cask Malbec, Mendoza, Argentina: hint of vanilla from oak aging, flavors of black cherries and black pepper, concentrated; $10.

Saturday, April 2, 2011

interview with Donald Hess

[from Verónica Gurisatti @ Brando, 2 April 2011]

"Los mejores Malbec y Torrontés se hacen en la Argentina"

El bodeguero suizo más famoso del momento, propietario de las bodegas salteñas Amalaya y Colomé habla sobre el mundo del vino a nivel mundial

Donald Hess es uno de los grandes referentes de la industria vitivinícola mundial y el presidente del grupo Hess Family Estate. Nació en Suiza, tiene 73 años y es propietario de siete bodegas en el mundo: tres en California (Sequana, Artezin y Monte Veeder), una en Sudáfrica (Glen Carlou), una en Australia (Peter Lehmann) y dos en Argentina (Colomé y Amalaya) en los Valles Calchaquíes. Además, es uno de los coleccionistas de arte contemporáneo más importantes del mundo.

Atraído por el paisaje y el desafío de producir vinos de alta calidad, en febrero del 2001 invirtió en la Argentina y compró la bodega Colomé en Salta (con los viñedos más altos del mundo a 2.300 metros de altura), luego inauguró un museo de arte contemporáneo y en diciembre del 2010 abrió Amalaya, su segunda bodega salteña, en el Divisadero. Si bien es conciente del enorme desafío que representa, está convencido de poder llevar adelante un plan de desarrollo económico y social.

Desde sus comienzos, Hess demostró una visión muy particular desarrollando como base importante del crecimiento tres principios fundamentales: calidad, cuidado del medio ambiente y compromiso social. Hoy, además de generar alternativas y oportunidades de trabajo, sirve como modelo para inspirar a otros. Pero no depende únicamente de su actitud, sino también del contexto nacional y global, y hoy la vitivinicultura es un negocio que crece al ritmo del mercado.

Algunos días atrás estuvo en Buenos Aires y habló con ConexiónBrando. Acá nos cuenta por qué decidió invertir en la Argentina y cómo se renueva día a día su empresa familiar.

ConexiónBrando: ¿Por qué decidió invertir en la Argentina?

Hess: Porque yo pienso en términos de variedades y como ya hago Cabernet Sauvignon y Chardonnay en California y Syrah en Australia, quería hacer Malbec y Torrontés, y el mejor lugar es la Argentina. Llegué al país por primera vez en el año 1983 y, casi por casualidad, mientras buscaba tierras cultivables para producir vinos, descubrí la bodega Colomé. La finca de 39.000 hectáreas tenía vida propia, pueblo propio, cultura propia e inmediatamente me cautivó.

¿Qué fue lo primero que le impactó del país?

Lo primero que me impactó, enológicamente hablando, fue el Malbec, aunque por esa época no se hablaba tanto de la variedad, tal vez por falta de confianza de parte de los productores en su potencial, pero a mí me encantó de entrada. Por eso en Colomé desarrollé ciento por ciento Malbec y también Torrontés porque creo que hay que enfocarse en uvas que tengan una identidad bien argentina y en un mundo tan globalizado hay que aprovechar la posibilidad de tener algo único.

¿Qué cambios observó en la industria desde su primera visita?

Es notable como mejoró la calidad, hoy casi no hay vinos con fallas. Antes eran sobremaduros, les faltaba frescura y no tenían la fruta que tienen hoy. Ahora, sin perder la intensidad son más elegantes, equilibrados y menos rústicos. En los últimos años se desarrollaron una serie de bodegas boutique con un enfoque bien claro hacia la calidad, y esto ayuda a crear la imagen de una industria más heterogénea y diversa frente a las bodegas grandes que lideran la exportación.

¿Cuándo empezó en el negocio del vino?

Si bien mi familia fue propietaria de una pequeña bodega en Suiza, recién en 1978 comencé a establecerme en distintas partes del mundo para producir vinos premium. Mi familia es originaria de la ciudad de Berna y durante ocho generaciones se dedicaron a la fabricación de cerveza y la hotelería. Yo empecé haciendo cerveza artesanal en Suiza, después embotellé agua mineral y recién después me dediqué al vino.

¿Cómo definiría el estilo de sus vinos salteños?

Son vinos de terroir, con carácter e identidad. El potencial de calidad que tiene el norte argentino es enorme, posee condiciones únicas como altitud, intensidad luminosa, amplitud térmica, clima seco, suelos con buen drenaje y muchos viñedos de setenta a ochenta años que producen uvas de una increíble calidad. Cada día son mejores y los resultados en el mercado internacional hablan por sí solos.

¿Qué es exactamente el terroir?

Es un concepto fundamental cuando se hace vino de calidad y es lo que lo diferencia de otras bebidas industriales. El vino es el resultado de muchas variables (humanas, culturales, climáticas y de suelo) y todas son importantes para definir su personalidad. En un sentido clásico, incluye el suelo y el clima que, obviamente, tienen un peso significativo, pero el terroir implica algo más: la gente con su cultura, su modo de hacer las cosas y sus tradiciones, ya que el vino es la expresión de la comunidad que lo hace.

¿Qué tienen en común la industria del arte y del vino?

La pasión y la gente. A mí me gusta comer con los artistas, hablar con ellos y conocer personalmente a cada autor de mi colección. Comencé a comprar arte contemporáneo hace más de 40 años y en 1989 abrí mi primer museo en el valle de Napa dentro de la bodega, luego otro en Glen Carlou en Sudáfrica y en el 2009 inauguré el tercero en la bodega Colomé dedicado íntegramente a la obra de James Turrell. Ahora estoy construyendo el cuarto en Australia.

¿Cómo es su domingo ideal?

Me gusta mucho ir a la montaña, hacer cabalgatas y compartir con amigos actividades al aire libre. El contacto con la naturaleza es fundamental, me permite encontrar la cordura y tener una escala de valores real. Los tiempos reales y las dimensiones reales son los de la naturaleza no los del ser humano.

"Los mejores Malbec y Torrontés se hacen en la Argentina"

El bodeguero suizo más famoso del momento, propietario de las bodegas salteñas Amalaya y Colomé habla sobre el mundo del vino a nivel mundial

Donald Hess es uno de los grandes referentes de la industria vitivinícola mundial y el presidente del grupo Hess Family Estate. Nació en Suiza, tiene 73 años y es propietario de siete bodegas en el mundo: tres en California (Sequana, Artezin y Monte Veeder), una en Sudáfrica (Glen Carlou), una en Australia (Peter Lehmann) y dos en Argentina (Colomé y Amalaya) en los Valles Calchaquíes. Además, es uno de los coleccionistas de arte contemporáneo más importantes del mundo.

Atraído por el paisaje y el desafío de producir vinos de alta calidad, en febrero del 2001 invirtió en la Argentina y compró la bodega Colomé en Salta (con los viñedos más altos del mundo a 2.300 metros de altura), luego inauguró un museo de arte contemporáneo y en diciembre del 2010 abrió Amalaya, su segunda bodega salteña, en el Divisadero. Si bien es conciente del enorme desafío que representa, está convencido de poder llevar adelante un plan de desarrollo económico y social.

Desde sus comienzos, Hess demostró una visión muy particular desarrollando como base importante del crecimiento tres principios fundamentales: calidad, cuidado del medio ambiente y compromiso social. Hoy, además de generar alternativas y oportunidades de trabajo, sirve como modelo para inspirar a otros. Pero no depende únicamente de su actitud, sino también del contexto nacional y global, y hoy la vitivinicultura es un negocio que crece al ritmo del mercado.

Algunos días atrás estuvo en Buenos Aires y habló con ConexiónBrando. Acá nos cuenta por qué decidió invertir en la Argentina y cómo se renueva día a día su empresa familiar.

ConexiónBrando: ¿Por qué decidió invertir en la Argentina?

Hess: Porque yo pienso en términos de variedades y como ya hago Cabernet Sauvignon y Chardonnay en California y Syrah en Australia, quería hacer Malbec y Torrontés, y el mejor lugar es la Argentina. Llegué al país por primera vez en el año 1983 y, casi por casualidad, mientras buscaba tierras cultivables para producir vinos, descubrí la bodega Colomé. La finca de 39.000 hectáreas tenía vida propia, pueblo propio, cultura propia e inmediatamente me cautivó.

¿Qué fue lo primero que le impactó del país?

Lo primero que me impactó, enológicamente hablando, fue el Malbec, aunque por esa época no se hablaba tanto de la variedad, tal vez por falta de confianza de parte de los productores en su potencial, pero a mí me encantó de entrada. Por eso en Colomé desarrollé ciento por ciento Malbec y también Torrontés porque creo que hay que enfocarse en uvas que tengan una identidad bien argentina y en un mundo tan globalizado hay que aprovechar la posibilidad de tener algo único.

¿Qué cambios observó en la industria desde su primera visita?

Es notable como mejoró la calidad, hoy casi no hay vinos con fallas. Antes eran sobremaduros, les faltaba frescura y no tenían la fruta que tienen hoy. Ahora, sin perder la intensidad son más elegantes, equilibrados y menos rústicos. En los últimos años se desarrollaron una serie de bodegas boutique con un enfoque bien claro hacia la calidad, y esto ayuda a crear la imagen de una industria más heterogénea y diversa frente a las bodegas grandes que lideran la exportación.

¿Cuándo empezó en el negocio del vino?

Si bien mi familia fue propietaria de una pequeña bodega en Suiza, recién en 1978 comencé a establecerme en distintas partes del mundo para producir vinos premium. Mi familia es originaria de la ciudad de Berna y durante ocho generaciones se dedicaron a la fabricación de cerveza y la hotelería. Yo empecé haciendo cerveza artesanal en Suiza, después embotellé agua mineral y recién después me dediqué al vino.

¿Cómo definiría el estilo de sus vinos salteños?

Son vinos de terroir, con carácter e identidad. El potencial de calidad que tiene el norte argentino es enorme, posee condiciones únicas como altitud, intensidad luminosa, amplitud térmica, clima seco, suelos con buen drenaje y muchos viñedos de setenta a ochenta años que producen uvas de una increíble calidad. Cada día son mejores y los resultados en el mercado internacional hablan por sí solos.

¿Qué es exactamente el terroir?

Es un concepto fundamental cuando se hace vino de calidad y es lo que lo diferencia de otras bebidas industriales. El vino es el resultado de muchas variables (humanas, culturales, climáticas y de suelo) y todas son importantes para definir su personalidad. En un sentido clásico, incluye el suelo y el clima que, obviamente, tienen un peso significativo, pero el terroir implica algo más: la gente con su cultura, su modo de hacer las cosas y sus tradiciones, ya que el vino es la expresión de la comunidad que lo hace.

¿Qué tienen en común la industria del arte y del vino?

La pasión y la gente. A mí me gusta comer con los artistas, hablar con ellos y conocer personalmente a cada autor de mi colección. Comencé a comprar arte contemporáneo hace más de 40 años y en 1989 abrí mi primer museo en el valle de Napa dentro de la bodega, luego otro en Glen Carlou en Sudáfrica y en el 2009 inauguré el tercero en la bodega Colomé dedicado íntegramente a la obra de James Turrell. Ahora estoy construyendo el cuarto en Australia.

¿Cómo es su domingo ideal?

Me gusta mucho ir a la montaña, hacer cabalgatas y compartir con amigos actividades al aire libre. El contacto con la naturaleza es fundamental, me permite encontrar la cordura y tener una escala de valores real. Los tiempos reales y las dimensiones reales son los de la naturaleza no los del ser humano.

Vik

Estancia Vik & Playa Vik are luxury art hotels, two more reasons to visit Uruguay.

Also, don't miss Vik Holistic Vineyard in Chile.

Some pix of Estancia Vik.

Also, don't miss Vik Holistic Vineyard in Chile.

Some pix of Estancia Vik.

|

| parilla & dining room |

|

| living room |

|

| bathtub |

Tuesday, March 8, 2011

rain

Today is the second day of a 2-day Argentine holiday, a brand new holiday on the seemingly endless slate of Argentine holidays, this one to celebrate Carnaval.

Yesterday we moved out of Ginny's La Estancia house into a rental house in town, a block off the plaza. The house is a series of rooms off a large courtyard. In the night through the wide open windows of our bedroom we heard the hammering of rain & behind it, music & revelry in the plaza.

People are complaining about the rain because it has gone on nearly every day for more than two months, because it is delaying the grape harvest, because it seemed as though it had stopped, because rain this time of year is not normal, because people complain about rain.

I love rain.

Yesterday we moved out of Ginny's La Estancia house into a rental house in town, a block off the plaza. The house is a series of rooms off a large courtyard. In the night through the wide open windows of our bedroom we heard the hammering of rain & behind it, music & revelry in the plaza.

People are complaining about the rain because it has gone on nearly every day for more than two months, because it is delaying the grape harvest, because it seemed as though it had stopped, because rain this time of year is not normal, because people complain about rain.

I love rain.

Wednesday, February 2, 2011

Torrontes

[from Eric Asimov at The New York Times, 1 February, 2011, thank you David Galland]

Ready for the Next Argentine Invasion?

TORRONTÉS has been touted as the hottest thing to arrive from Argentina since the tango. Or at least since malbec. It’s a grape, and a white wine, and some say it will be as popular in the United States as pinot grigio.

Well, one day, perhaps. But first things first. Have you even heard of torrontés? The grape is grown pretty much nowhere else in the world but Argentina. Yes, Spain also has a grape called torrontés, but the two grapes are apparently unrelated. The Argentine grape has been shown genetically to be a hybrid of the muscat of Alexandria and the criolla, or mission, as it’s known in English.

The ancestry of the torrontés is interesting only in that it most definitely bears more than a passing resemblance to the gloriously fragrant muscat. The best torrontés are highly aromatic, exuberantly floral with a rich, hothouse citrus scent as well. Dip your nose into a glass, and you don’t know whether it ought to be sold as a wine or a perfume.

Argentina has a talent for obscure grapes. It took the malbec, a red grape that is forgotten in Bordeaux, overlooked in Cahors and known as côt in the Loire Valley, and turned it into a juicy, fruity, money-generating phenomenon identified purely with Argentina. Can torrontés become malbec’s white counterpart?

Indeed, in 2010, Argentina exported more than 231,000 cases of torrontés to the United States, according to Wines of Argentina, a trade group. That figure may seem minuscule next to the 3.15 million cases of Argentine malbec the United States received that year. But compared with the mere 29,333 cases of torrontés exported to the United States in 2004, the growth has been remarkable.

Given the rate of the torrontés onslaught, the wine panel felt compelled recently to taste through 20 bottles. We could easily have done 50, given the sheer amount of wine out there. For the tasting, Florence Fabricant and I were joined by Brett Feore, the beverage director at Apiary in the East Village, and Carla Rzeszewski, the wine director at the Breslin and the John Dory Oyster Bar on West 29th Street.

It was clear right away that torrontés has issues of identity. These wines were all over the stylistic map. Some were indeed dry, light-bodied and crisp, like pinot grigios. Others were broad, heavy and rich, like ultra-ripe California chardonnays.

This may be a problem. All genres of wine have their stylistic deviations, but consumers can often read the cues. Chablis is a chardonnay that one can reasonably assume will be lean and minerally, without oak flavors. One would likewise expect a California chardonnay to be richer, and oaky flavors would not surprise. Of course, exceptions exist, often from labels that have been around long enough to establish an identity of their own. But torrontés has no clear identity, not yet at least, and the unpredictable nature of what’s in the bottles will not help.

Wherever the wines landed on the spectrum, we found that their level of quality depended on one crucial component: acidity. Whether light or heavy, if the wines had enough acidity they came across as lively and vivacious. The rest landed with a thud, flaccid, unctuous and unpleasant.

Florence had other issues with the wines. “Some were concentrated, but finished with a kind of watery emptiness,” she said. “And often, the nose and the palate were not on speaking terms.” That is to say, the aromas often did not signal clearly how the wines would taste.

So, what did we like? Those beautiful aromas — or as Brett put it, “floral, mandarin, muscat, nice!” Carla found a touch of bitterness in some wines, which she very much appreciated.

Just to make torrontés a little more complicated, it turns out the grape in Argentina has three sub-varieties: the torrontés Riojano, the best and most aromatic, which comes from the northern province of La Rioja and Salta; the less aromatic torrontés Sanjuanino, from the San Juan province south of La Rioja; and the much-less aromatic torrontés Mendocino, from the Mendoza area, which — fasten your seat belts — may not be related to the other two at all.

While I would never want to assume which sub-variety was used, we did find a geographical correlation. Of the 20 bottles in the tasting, 11 were from Salta and other northern provinces. Eight were from Mendoza, and one was from San Juan. But of our top 10, seven were from the north, including our top four. Only three were from Mendoza, and they tended to be more subdued aromatically.

Our No. 1 wine, and our best value at $15, was the 2009 Cuma from Michel Torino, from the Cafayate Valley in Salta. With plenty of acidity, the Cuma was fresh and lively, which made its aromas of mandarin and cantaloupe vibrant rather than heavy. Likewise, our No. 2, the 2009 Alamos from Catena, also from Salta, was thoroughly refreshing with aromas of orange blossoms.

The story was similar for Nos. 3 and 4, both from Salta, too. The 2010 Crios de Susana Balbo was fragrant with melon and citrus, and well balanced, as was the 2009 Tomás Achával Nómade, which had an added herbal touch. By contrast the No. 5 Norton Lo Tengo and the No. 6 Goulart, both from Mendoza, were far more reticent aromatically though pleasing and balanced enough.

At this stage in the evolution of torrontés quite a bit of experimentation is still going on. Some wines are clearly made in steel tanks, which accentuates the fresh, lively aromas. Others may have been briefly aged in oak barrels, adding depth and texture to the wines. Thankfully, we found very little evidence of new oak in our tasting.

For my part, I was encouraged by the wines we liked best, particularly our top five. Their aromatic exuberance is singular and pleasing, with the caution that the wines ought to be consumed while young. As for comparisons to pinot grigio, they seem both premature and misleading. The big-selling pinot grigios are so indistinct that they offend no one but those seeking distinctive wines. Torrontés, on the other hand, are quite unusual, which confers on them the power to offend. In wine, that’s often a good thing.

Tasting Report

BEST VALUE

Michel Torino Cuma, $15, ***

Cafayate Valley Torrontés 2009

Fresh and lively with depth, presence and flavors of orange and cantaloupe. (Frederick Wildman & Sons, New York)

Catena Alamos, $14, ***

Salta Torrontés 2009

Fragrant and refreshing with aromas of flowers and citrus. (Alamos U.S.A., Hayward, Calif.)

Crios de Susana Balbo, $13, ** ½

Salta Torrontés 2010

Well balanced with lingering flavors of mandarin and honeydew. (Vine Connections, Sausalito, Calif.)

Tomás Achával Nómade, $17, ** ½

Cafayate Valley Torrontés 2009

Light-bodied and balanced with floral aromas and orange and herbal flavors. (Domaine Select Wine Estates, New York)

Norton Lo Tengo, $11, ** ½

Mendoza Torrontés 2009

Full-bodied but fresh and balanced with flavors of citrus and tropical fruit. (Tgic Importers, Woodland Hills, Calif.)

Goulart, $14, **

Mendoza Torrontés 2009

Subtle and restrained with flavors of minerals, melon and herbs. (Southern Starz, Huntington Beach, Calif.)

Colomé Calchaquí Valley, $12, **

Torrontés 2009

Balanced and pleasing with flavors of peaches, flowers and citrus. (The Hess Wine Collection, Napa, Calif.)

La Yunta Famatina Valley, $10, **

La Rioja Torrontés 2010

Straightforward with orange and herbal flavors. (SWG Imports, Bend, Ore.)

San Telmo Esencia, $15, **

Mendoza Torrontés 2009

Flavors of melon and citrus but a bit heavy. (Diageo Chateau & Estate Wines, Napa, Calif.)

Terrazas de los Andes, $21, **

Reserva Salta Torrontés 2008

Aromas of ripe oranges and flowers but a touch hot. (Moët-Hennessy, New York)

Ready for the Next Argentine Invasion?

TORRONTÉS has been touted as the hottest thing to arrive from Argentina since the tango. Or at least since malbec. It’s a grape, and a white wine, and some say it will be as popular in the United States as pinot grigio.

Well, one day, perhaps. But first things first. Have you even heard of torrontés? The grape is grown pretty much nowhere else in the world but Argentina. Yes, Spain also has a grape called torrontés, but the two grapes are apparently unrelated. The Argentine grape has been shown genetically to be a hybrid of the muscat of Alexandria and the criolla, or mission, as it’s known in English.

The ancestry of the torrontés is interesting only in that it most definitely bears more than a passing resemblance to the gloriously fragrant muscat. The best torrontés are highly aromatic, exuberantly floral with a rich, hothouse citrus scent as well. Dip your nose into a glass, and you don’t know whether it ought to be sold as a wine or a perfume.

Argentina has a talent for obscure grapes. It took the malbec, a red grape that is forgotten in Bordeaux, overlooked in Cahors and known as côt in the Loire Valley, and turned it into a juicy, fruity, money-generating phenomenon identified purely with Argentina. Can torrontés become malbec’s white counterpart?

Indeed, in 2010, Argentina exported more than 231,000 cases of torrontés to the United States, according to Wines of Argentina, a trade group. That figure may seem minuscule next to the 3.15 million cases of Argentine malbec the United States received that year. But compared with the mere 29,333 cases of torrontés exported to the United States in 2004, the growth has been remarkable.

Given the rate of the torrontés onslaught, the wine panel felt compelled recently to taste through 20 bottles. We could easily have done 50, given the sheer amount of wine out there. For the tasting, Florence Fabricant and I were joined by Brett Feore, the beverage director at Apiary in the East Village, and Carla Rzeszewski, the wine director at the Breslin and the John Dory Oyster Bar on West 29th Street.

It was clear right away that torrontés has issues of identity. These wines were all over the stylistic map. Some were indeed dry, light-bodied and crisp, like pinot grigios. Others were broad, heavy and rich, like ultra-ripe California chardonnays.

This may be a problem. All genres of wine have their stylistic deviations, but consumers can often read the cues. Chablis is a chardonnay that one can reasonably assume will be lean and minerally, without oak flavors. One would likewise expect a California chardonnay to be richer, and oaky flavors would not surprise. Of course, exceptions exist, often from labels that have been around long enough to establish an identity of their own. But torrontés has no clear identity, not yet at least, and the unpredictable nature of what’s in the bottles will not help.

Wherever the wines landed on the spectrum, we found that their level of quality depended on one crucial component: acidity. Whether light or heavy, if the wines had enough acidity they came across as lively and vivacious. The rest landed with a thud, flaccid, unctuous and unpleasant.

Florence had other issues with the wines. “Some were concentrated, but finished with a kind of watery emptiness,” she said. “And often, the nose and the palate were not on speaking terms.” That is to say, the aromas often did not signal clearly how the wines would taste.

So, what did we like? Those beautiful aromas — or as Brett put it, “floral, mandarin, muscat, nice!” Carla found a touch of bitterness in some wines, which she very much appreciated.

Just to make torrontés a little more complicated, it turns out the grape in Argentina has three sub-varieties: the torrontés Riojano, the best and most aromatic, which comes from the northern province of La Rioja and Salta; the less aromatic torrontés Sanjuanino, from the San Juan province south of La Rioja; and the much-less aromatic torrontés Mendocino, from the Mendoza area, which — fasten your seat belts — may not be related to the other two at all.

While I would never want to assume which sub-variety was used, we did find a geographical correlation. Of the 20 bottles in the tasting, 11 were from Salta and other northern provinces. Eight were from Mendoza, and one was from San Juan. But of our top 10, seven were from the north, including our top four. Only three were from Mendoza, and they tended to be more subdued aromatically.

Our No. 1 wine, and our best value at $15, was the 2009 Cuma from Michel Torino, from the Cafayate Valley in Salta. With plenty of acidity, the Cuma was fresh and lively, which made its aromas of mandarin and cantaloupe vibrant rather than heavy. Likewise, our No. 2, the 2009 Alamos from Catena, also from Salta, was thoroughly refreshing with aromas of orange blossoms.

The story was similar for Nos. 3 and 4, both from Salta, too. The 2010 Crios de Susana Balbo was fragrant with melon and citrus, and well balanced, as was the 2009 Tomás Achával Nómade, which had an added herbal touch. By contrast the No. 5 Norton Lo Tengo and the No. 6 Goulart, both from Mendoza, were far more reticent aromatically though pleasing and balanced enough.

At this stage in the evolution of torrontés quite a bit of experimentation is still going on. Some wines are clearly made in steel tanks, which accentuates the fresh, lively aromas. Others may have been briefly aged in oak barrels, adding depth and texture to the wines. Thankfully, we found very little evidence of new oak in our tasting.

For my part, I was encouraged by the wines we liked best, particularly our top five. Their aromatic exuberance is singular and pleasing, with the caution that the wines ought to be consumed while young. As for comparisons to pinot grigio, they seem both premature and misleading. The big-selling pinot grigios are so indistinct that they offend no one but those seeking distinctive wines. Torrontés, on the other hand, are quite unusual, which confers on them the power to offend. In wine, that’s often a good thing.

Tasting Report

BEST VALUE

Michel Torino Cuma, $15, ***

Cafayate Valley Torrontés 2009

Fresh and lively with depth, presence and flavors of orange and cantaloupe. (Frederick Wildman & Sons, New York)

Catena Alamos, $14, ***

Salta Torrontés 2009

Fragrant and refreshing with aromas of flowers and citrus. (Alamos U.S.A., Hayward, Calif.)

Crios de Susana Balbo, $13, ** ½

Salta Torrontés 2010

Well balanced with lingering flavors of mandarin and honeydew. (Vine Connections, Sausalito, Calif.)

Tomás Achával Nómade, $17, ** ½

Cafayate Valley Torrontés 2009

Light-bodied and balanced with floral aromas and orange and herbal flavors. (Domaine Select Wine Estates, New York)

Norton Lo Tengo, $11, ** ½

Mendoza Torrontés 2009

Full-bodied but fresh and balanced with flavors of citrus and tropical fruit. (Tgic Importers, Woodland Hills, Calif.)

Goulart, $14, **

Mendoza Torrontés 2009

Subtle and restrained with flavors of minerals, melon and herbs. (Southern Starz, Huntington Beach, Calif.)

Colomé Calchaquí Valley, $12, **

Torrontés 2009

Balanced and pleasing with flavors of peaches, flowers and citrus. (The Hess Wine Collection, Napa, Calif.)

La Yunta Famatina Valley, $10, **

La Rioja Torrontés 2010

Straightforward with orange and herbal flavors. (SWG Imports, Bend, Ore.)

San Telmo Esencia, $15, **

Mendoza Torrontés 2009

Flavors of melon and citrus but a bit heavy. (Diageo Chateau & Estate Wines, Napa, Calif.)

Terrazas de los Andes, $21, **

Reserva Salta Torrontés 2008

Aromas of ripe oranges and flowers but a touch hot. (Moët-Hennessy, New York)

Tuesday, January 25, 2011

buying a vineyard in Mendoza

[from Bloomberg, 25 January 2011, thank you to Steve Abramowitz]

Argentina Lures Bankers Dreaming of Owning Their Own Vineyard

For his 50th birthday two years ago, Phil Asmundson, vice chairman of technology at Deloitte LLP, flew to Argentina for a vacation and ended up buying a vineyard.

As a long-time wine collector, making his own was a secret dream. During harvest in March or April, he'll fly down from New York to pick malbec grapes and play cellar rat.

Asmundson bought 3 acres of land in the Uco Valley for just under $200,000 from Vines of Mendoza, a five-year-old company in Argentina that sells parcels of prime vineyard acreage, plants them to owners' specifications, then manages caretaking and winemaking. Owners can participate as much or as little as they wish. The 87 so far come from 7 states and 9 countries.

"There aren't many passions that are made easy to do," says Asmundson. "This was turnkey."

The other deciding factors? He loves the country's signature malbec grape, and was persuaded that the wines could be "really great quality" because Vines of Mendoza has the help of well-known winemaker Santiago Achaval.

When the deal was final, he and his wife celebrated with bottles of Salentein Primus malbec ($45) from Argentina and Heitz Trailside cabernet ($80) from Napa.

Vines of Mendoza sent him a case of unmarked wines to taste, and used his notes to help focus the style of wine he wanted to make.

Luxury Resort

On a freezing December day, I caught up on the latest developments with co-founder Michael Evans, 45, bronzed from days in vineyard sun, at Manhattan's Topaz Thai restaurant. Over a spicy salad lunch, he clicked through drawings on his laptop of the company's new luxury resort, opening in 2012, where vineyard owners like Asmundson can stay while playing vintner, and tourists can be part of the wine lifestyle.

Lots of glass, local stone, a tiny wine blending lab, courses on Argentine wines—it looked like ambitious high-end Napa with South American cowhide flair and a breathtaking snowcapped Andes backdrop. What started in 2005 as a way for Evans, now 45, to afford his personal vineyard-owning dream has expanded into a range of ventures.

"I alternated between working in wireless technology and politics, but was also passionate about wine," he said.

Exhausted by the John Kerry presidential campaign, he was vacationing in Argentina when he was introduced to Pablo Gimenez Riili by a bookseller in Buenos Aires. The two became business partners and in 2006, after looking at 76 pieces of land, they settled on 1,000 acres accessible only by horseback in the Uco Valley south of the city of Mendoza, near top wineries Bodegas Salentein and Clos de la Siete.

Financial Crash

They ran up credit card debt and tapped friends, family, and angels for $5 million in costs and $500,000 in legal fees, and started offering 3 to 18-acre parcels in 2007. More than 50 of the total 100 sold quickly, but all stalled in 2008.

"You don't know how hard it is to sell a $200,000 vineyard when the financial world is crashing," Evans said. In 2010, though, they unloaded another 25. Planting 1.3 million vines, building a winery, and more has cost another $15 million.

There are hundreds of wineries in the Mendoza region, but on my first trip in 2001, there was no wine bar in Mendoza city where you could taste the best. So Vines of Mendoza opened The Tasting Room in March 2007, then a retail shop and wine bar in the city's Park Hyatt hotel in 2008. They started a wine club, with a warehouse in Napa and recently added a downloadable insider's guide to the region on the Vines of Mendoza website.

Mid-Life Crisis

Judging from the emails I receive, the owning-a-vineyard fantasy is especially popular among wine lovers in midlife crisis mode looking for a life-change. There are now dozens of projects catering to them.

In Oregon wine country near McMinnville is just-launched Hyland Vineyard Estates, a 154-acre project where winemaker Laurent Montalieu is offering homesites with already planted vines he'll manage for $700,000 to more than $1 million. Planned communities of home-plus-vineyard are also being sold in Portugal's Alentejo and France's Languedoc regions.

Evans sent me a barrel sample of Vines of Mendoza's first wine, a blend of owners' malbec grapes, that will be released in March. It was smooth and balanced with lots of dark fruit and earth flavors, though it certainly wasn't the best Argentine malbec I've had.

"It's not only people with 3,000 bottle cellars who buy, says Evans. "These are investment bankers, doctors looking for participatory vacations." And, of course the chance to make wine they'd like to put their name on.

Restaurateur Puck

They also include restaurateur Wolfgang Puck and a Napa vintner. London-based Nick Smith originally bought in for investment but says owning his 3 acres has turned him into passionate wine buff.

Just after Christmas I received a holiday e-mail from Evans, who was back home in Mendoza with his chocolate Labrador, throwing meat on the grill for friends at his regular Sunday asados. He sent a beautiful photo of sunrise over the company's vineyards in Mendoza. Outside my door was a foot of snow.

I remembered a comment from Asmundson, whose wine, from bought grapes, is now in barrel and will be bottled in 2012 in time to serve at Thanksgiving.

"When I think about my vineyard, I smile," he said. "I just wish I'd bought 5 acres."

Argentina Lures Bankers Dreaming of Owning Their Own Vineyard

For his 50th birthday two years ago, Phil Asmundson, vice chairman of technology at Deloitte LLP, flew to Argentina for a vacation and ended up buying a vineyard.

As a long-time wine collector, making his own was a secret dream. During harvest in March or April, he'll fly down from New York to pick malbec grapes and play cellar rat.

Asmundson bought 3 acres of land in the Uco Valley for just under $200,000 from Vines of Mendoza, a five-year-old company in Argentina that sells parcels of prime vineyard acreage, plants them to owners' specifications, then manages caretaking and winemaking. Owners can participate as much or as little as they wish. The 87 so far come from 7 states and 9 countries.

"There aren't many passions that are made easy to do," says Asmundson. "This was turnkey."

The other deciding factors? He loves the country's signature malbec grape, and was persuaded that the wines could be "really great quality" because Vines of Mendoza has the help of well-known winemaker Santiago Achaval.

When the deal was final, he and his wife celebrated with bottles of Salentein Primus malbec ($45) from Argentina and Heitz Trailside cabernet ($80) from Napa.

Vines of Mendoza sent him a case of unmarked wines to taste, and used his notes to help focus the style of wine he wanted to make.

Luxury Resort

On a freezing December day, I caught up on the latest developments with co-founder Michael Evans, 45, bronzed from days in vineyard sun, at Manhattan's Topaz Thai restaurant. Over a spicy salad lunch, he clicked through drawings on his laptop of the company's new luxury resort, opening in 2012, where vineyard owners like Asmundson can stay while playing vintner, and tourists can be part of the wine lifestyle.

Lots of glass, local stone, a tiny wine blending lab, courses on Argentine wines—it looked like ambitious high-end Napa with South American cowhide flair and a breathtaking snowcapped Andes backdrop. What started in 2005 as a way for Evans, now 45, to afford his personal vineyard-owning dream has expanded into a range of ventures.

"I alternated between working in wireless technology and politics, but was also passionate about wine," he said.

Exhausted by the John Kerry presidential campaign, he was vacationing in Argentina when he was introduced to Pablo Gimenez Riili by a bookseller in Buenos Aires. The two became business partners and in 2006, after looking at 76 pieces of land, they settled on 1,000 acres accessible only by horseback in the Uco Valley south of the city of Mendoza, near top wineries Bodegas Salentein and Clos de la Siete.

Financial Crash

They ran up credit card debt and tapped friends, family, and angels for $5 million in costs and $500,000 in legal fees, and started offering 3 to 18-acre parcels in 2007. More than 50 of the total 100 sold quickly, but all stalled in 2008.

"You don't know how hard it is to sell a $200,000 vineyard when the financial world is crashing," Evans said. In 2010, though, they unloaded another 25. Planting 1.3 million vines, building a winery, and more has cost another $15 million.

There are hundreds of wineries in the Mendoza region, but on my first trip in 2001, there was no wine bar in Mendoza city where you could taste the best. So Vines of Mendoza opened The Tasting Room in March 2007, then a retail shop and wine bar in the city's Park Hyatt hotel in 2008. They started a wine club, with a warehouse in Napa and recently added a downloadable insider's guide to the region on the Vines of Mendoza website.

Mid-Life Crisis

Judging from the emails I receive, the owning-a-vineyard fantasy is especially popular among wine lovers in midlife crisis mode looking for a life-change. There are now dozens of projects catering to them.

In Oregon wine country near McMinnville is just-launched Hyland Vineyard Estates, a 154-acre project where winemaker Laurent Montalieu is offering homesites with already planted vines he'll manage for $700,000 to more than $1 million. Planned communities of home-plus-vineyard are also being sold in Portugal's Alentejo and France's Languedoc regions.

Evans sent me a barrel sample of Vines of Mendoza's first wine, a blend of owners' malbec grapes, that will be released in March. It was smooth and balanced with lots of dark fruit and earth flavors, though it certainly wasn't the best Argentine malbec I've had.

"It's not only people with 3,000 bottle cellars who buy, says Evans. "These are investment bankers, doctors looking for participatory vacations." And, of course the chance to make wine they'd like to put their name on.

Restaurateur Puck

They also include restaurateur Wolfgang Puck and a Napa vintner. London-based Nick Smith originally bought in for investment but says owning his 3 acres has turned him into passionate wine buff.

Just after Christmas I received a holiday e-mail from Evans, who was back home in Mendoza with his chocolate Labrador, throwing meat on the grill for friends at his regular Sunday asados. He sent a beautiful photo of sunrise over the company's vineyards in Mendoza. Outside my door was a foot of snow.

I remembered a comment from Asmundson, whose wine, from bought grapes, is now in barrel and will be bottled in 2012 in time to serve at Thanksgiving.

"When I think about my vineyard, I smile," he said. "I just wish I'd bought 5 acres."

Wednesday, January 19, 2011

Argentine wine

[from Latin American Herald Tribune, 19 January 2011]

Argentina Pulls Ahead of Chile in Wine Exports to U.S.

BUENOS AIRES – Argentine wine exports to the United States topped those from neighboring Chile last year, spokespersons for the National Institute of Viniculture told Efe on Tuesday.

Argentina exported $222 million worth of wine to the United States in 2010, compared with $210 million for Chile.

Total foreign sales of Argentine wine exceeded $860 million last year, up 12 percent from 2009, when a poor harvest blamed on bad weather forced Argentina to import Chilean wine to meet domestic demand.

Argentina now ranks fourth, behind Italy, France and Australia, as a supplier of wine to the U.S. market.

“It’s good news, but no more than that. The important thing is that, at an adverse moment, Argentina continued growing,” the director of the Bodegas de Argentina vintners association, Juan Carlos Pina, told Buenos Aires daily Clarin.

“The recession in the U.S. made people stop consuming European wines” and the search for “other options” led them to Argentina’s Malbec variety, vintner Jose Zuccardi said.

While Bodegas de Argentina president Angel Vespa pointed out that Chile’s wine exporters were hurt by the rise of the Chilean peso against the dollar.

Wine was proclaimed Argentina’s “national beverage” in November, a nod to the importance of an industry that generates $2.63 billion in annual sales and employs around 400,000 people.

Argentina is the world’s No. 5 producer of wine, ninth-biggest exporter and ranks seventh globally in consumption, even though Argentines’ annual per capita wine intake has fallen from 90 liters to 30 liters over the last 40 years.

More than three-quarters of Argentine wine production is consumed domestically.

Argentina Pulls Ahead of Chile in Wine Exports to U.S.

BUENOS AIRES – Argentine wine exports to the United States topped those from neighboring Chile last year, spokespersons for the National Institute of Viniculture told Efe on Tuesday.

Argentina exported $222 million worth of wine to the United States in 2010, compared with $210 million for Chile.

Total foreign sales of Argentine wine exceeded $860 million last year, up 12 percent from 2009, when a poor harvest blamed on bad weather forced Argentina to import Chilean wine to meet domestic demand.

Argentina now ranks fourth, behind Italy, France and Australia, as a supplier of wine to the U.S. market.

“It’s good news, but no more than that. The important thing is that, at an adverse moment, Argentina continued growing,” the director of the Bodegas de Argentina vintners association, Juan Carlos Pina, told Buenos Aires daily Clarin.

“The recession in the U.S. made people stop consuming European wines” and the search for “other options” led them to Argentina’s Malbec variety, vintner Jose Zuccardi said.

While Bodegas de Argentina president Angel Vespa pointed out that Chile’s wine exporters were hurt by the rise of the Chilean peso against the dollar.

Wine was proclaimed Argentina’s “national beverage” in November, a nod to the importance of an industry that generates $2.63 billion in annual sales and employs around 400,000 people.

Argentina is the world’s No. 5 producer of wine, ninth-biggest exporter and ranks seventh globally in consumption, even though Argentines’ annual per capita wine intake has fallen from 90 liters to 30 liters over the last 40 years.

More than three-quarters of Argentine wine production is consumed domestically.

Sunday, December 26, 2010

starting a vineyard outside of Mendoza

[from Yvonne & Tom Phelan in The Wall Street Journal, Dec. 20, 2010]

Moving to Argentina

We discovered Argentina three years ago, during what we assumed would be a brief visit to Buenos Aires. Today, we own a 108-acre vineyard outside Mendoza, a city and metropolitan area of about 800,000 people in western Argentina and our home for about 10 months out of each year.

How we came to live in Argentina is a story of good fortune, hard work—and considerable patience. Our adopted country, for all its charms, moves at its own, deliberate pace.

During our working years in the U.S. (primarily in real-estate investment), we lived in several places—California, Arizona, New York, Colorado—but never found our Shangri-La. Over time, the idea of living abroad became more appealing. We're restless and inquisitive by nature, and the chance to meet new people, be part of another culture and learn another language seemed to fit our needs.

In 2007, a three-day real-estate conference brought us to Buenos Aires. The atmosphere felt right from the start: a European-like mix of culture and numerous diversions, including, of course, the tango. We ended up renting an apartment for three months, which allowed us to explore Argentina's wine country and Mendoza.

Realizing a Dream

For decades, the two of us had shared a dream of owning a vineyard in California's Napa Valley. But by the time we reached our 60s and began investigating our dream in earnest, the five-acre property we envisioned owning and nurturing cost more than $1 million.

Mendoza, by contrast, was a revelation. Land outside the city, the unofficial capital of Argentina's growing wine industry, could be had for about $1,500 an acre (although prices have been climbing steadily since our arrival). At the same time, we found ourselves smitten with Mendoza itself: the many beautiful parks, the breathtaking views of the Andes Mountains, and the night life that spills out of restaurants and onto the sidewalks.

We decided to pursue our Napa Valley dream in Argentina.

Today, we divide our time between our vineyard, which is about a 2½-hour drive from Mendoza, and the city. As with any new business, the demands have been overwhelming at times. Between finding the right workers and staff (including a vineyard manager, an agronomist and an accountant) and the right supplies and equipment (including 40,000 grapevines, 6,000 fence posts, miles of trellis wire and a tractor), we have asked ourselves more than once: "Are we out of our minds?" Still, progress is evident: This year, we will have planted 43 acres of Malbec, Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah and Chardonnay grapes.

Eventually, when the grapevines are more mature, we plan to build a home at the vineyard. For now, we live on the 10th floor of a high-rise condominium building in Mendoza within easy walking distance of all our needs. We have panoramic views of the city and the Andes, as well as all of the amenities of a luxury residence in the U.S.—at about one-fifth the cost. Our monthly outlay for rent, utilities, cable-TV, telephone and Internet services is less than $1,000.

Quick Adjustment

We were fortunate in that we found our "sea legs" relatively quickly. Within a month or so of our arrival, we had a good feel for the center of the city. (Outlying areas are rarely more than a $5 cab ride away.) For the most part, Mendoza has proved to be more than hospitable. We frequently attend local functions—art exhibitions, wine tastings, jazz or tango music, cooking classes, poetry readings—where we mingle with Argentines and other expats.

(Yvonne was fluent in Spanish before we arrived in Argentina, although she has had to adjust to some pronunciations and vocabulary. Tom knows little Spanish and tends to rely on Yvonne.)

Weekends often find us choosing between a "city day" or a "country day." If it's the former, we might go the Central Market, built in 1883, where specialty vendors educate you about their offerings. If it's the latter, we might drive to a winery for lunch, with snow-capped mountains as a backdrop.

Cultural Differences

Of course, some culture shock was inevitable. Among the surprises:

• Foods that you crave but can't find. In particular, Chinese, Thai and Mexican dishes are tough to prepare because few places carry the ingredients.

• Appliances. They can be as much as 25% to 50% more expensive in Argentina than in the U.S.

• A lack of orderly and predictable business functions. You might be totally ignored at a restaurant during a shift change because all of the employees are busy listening to their shift supervisor. Or you might arrive at a retail store you have patronized many times only to find it closed during normal business hours for no apparent reason.

• The movies. You show up at the scheduled show time—but the movie hasn't arrived or the projectionist hasn't come to work. Or a movie is listed as playing in English when in fact it's playing in Spanish.

Nudge, Nudge

Much of this is simply a reflection of the "Argentine way." In the U.S., we're accustomed to initiating an action and getting a response. Many Argentines, to put it gently, don't adhere to that approach. You have to continually pursue them for a response or answer. They say, "Yes, yes, yes," but nothing will happen until, by sheer persistence, you finally get the answer or the problem is resolved.

Our style is to continually call, push to completion and be gracious when something actually gets done. Threats or loss of patience won't move Argentines. They move at their own pace, and nothing is so important to them that it speeds up that pace.

In many ways, we feel as if we have arrived in Argentina and Mendoza at the best of moments. The wine industry has pumped $15 billion into the city alone in recent years, which has helped build a formidable infrastructure—including excellent and affordable health care.

With services for doctors and dentists about 20% of the cost in the U.S., many expats self-insure. (Tom recently had an old crown removed, the tooth pulled, and a bone graft and implant done—all for $600.)

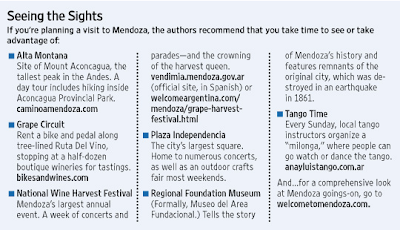

Each year, tens of thousands of foreigners flock to Mendoza to visit the region's 1,200 wineries. The biggest annual event in the city is the Fiesta Nacional de la Vendimia (the National Wine Harvest Festival) in early March. A week of concerts and parades culminate in the festival queen's coronation in the San Martin Park Amphitheater.

In all, we are very thankful that we found Mendoza, and that this lovely Argentine city has graciously embraced us. We envision a future where we will sit on the veranda of our "estancia" (farm or ranch house), sipping one of our Malbec wines, looking out at our vineyard and saying: "This is la vida buena."

Moving to Argentina

We discovered Argentina three years ago, during what we assumed would be a brief visit to Buenos Aires. Today, we own a 108-acre vineyard outside Mendoza, a city and metropolitan area of about 800,000 people in western Argentina and our home for about 10 months out of each year.

How we came to live in Argentina is a story of good fortune, hard work—and considerable patience. Our adopted country, for all its charms, moves at its own, deliberate pace.

During our working years in the U.S. (primarily in real-estate investment), we lived in several places—California, Arizona, New York, Colorado—but never found our Shangri-La. Over time, the idea of living abroad became more appealing. We're restless and inquisitive by nature, and the chance to meet new people, be part of another culture and learn another language seemed to fit our needs.

In 2007, a three-day real-estate conference brought us to Buenos Aires. The atmosphere felt right from the start: a European-like mix of culture and numerous diversions, including, of course, the tango. We ended up renting an apartment for three months, which allowed us to explore Argentina's wine country and Mendoza.

Realizing a Dream

For decades, the two of us had shared a dream of owning a vineyard in California's Napa Valley. But by the time we reached our 60s and began investigating our dream in earnest, the five-acre property we envisioned owning and nurturing cost more than $1 million.

Mendoza, by contrast, was a revelation. Land outside the city, the unofficial capital of Argentina's growing wine industry, could be had for about $1,500 an acre (although prices have been climbing steadily since our arrival). At the same time, we found ourselves smitten with Mendoza itself: the many beautiful parks, the breathtaking views of the Andes Mountains, and the night life that spills out of restaurants and onto the sidewalks.

We decided to pursue our Napa Valley dream in Argentina.

Today, we divide our time between our vineyard, which is about a 2½-hour drive from Mendoza, and the city. As with any new business, the demands have been overwhelming at times. Between finding the right workers and staff (including a vineyard manager, an agronomist and an accountant) and the right supplies and equipment (including 40,000 grapevines, 6,000 fence posts, miles of trellis wire and a tractor), we have asked ourselves more than once: "Are we out of our minds?" Still, progress is evident: This year, we will have planted 43 acres of Malbec, Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah and Chardonnay grapes.

Eventually, when the grapevines are more mature, we plan to build a home at the vineyard. For now, we live on the 10th floor of a high-rise condominium building in Mendoza within easy walking distance of all our needs. We have panoramic views of the city and the Andes, as well as all of the amenities of a luxury residence in the U.S.—at about one-fifth the cost. Our monthly outlay for rent, utilities, cable-TV, telephone and Internet services is less than $1,000.

Quick Adjustment

We were fortunate in that we found our "sea legs" relatively quickly. Within a month or so of our arrival, we had a good feel for the center of the city. (Outlying areas are rarely more than a $5 cab ride away.) For the most part, Mendoza has proved to be more than hospitable. We frequently attend local functions—art exhibitions, wine tastings, jazz or tango music, cooking classes, poetry readings—where we mingle with Argentines and other expats.

(Yvonne was fluent in Spanish before we arrived in Argentina, although she has had to adjust to some pronunciations and vocabulary. Tom knows little Spanish and tends to rely on Yvonne.)

Weekends often find us choosing between a "city day" or a "country day." If it's the former, we might go the Central Market, built in 1883, where specialty vendors educate you about their offerings. If it's the latter, we might drive to a winery for lunch, with snow-capped mountains as a backdrop.

Cultural Differences

Of course, some culture shock was inevitable. Among the surprises:

• Foods that you crave but can't find. In particular, Chinese, Thai and Mexican dishes are tough to prepare because few places carry the ingredients.

• Appliances. They can be as much as 25% to 50% more expensive in Argentina than in the U.S.

• A lack of orderly and predictable business functions. You might be totally ignored at a restaurant during a shift change because all of the employees are busy listening to their shift supervisor. Or you might arrive at a retail store you have patronized many times only to find it closed during normal business hours for no apparent reason.

• The movies. You show up at the scheduled show time—but the movie hasn't arrived or the projectionist hasn't come to work. Or a movie is listed as playing in English when in fact it's playing in Spanish.

Nudge, Nudge

Much of this is simply a reflection of the "Argentine way." In the U.S., we're accustomed to initiating an action and getting a response. Many Argentines, to put it gently, don't adhere to that approach. You have to continually pursue them for a response or answer. They say, "Yes, yes, yes," but nothing will happen until, by sheer persistence, you finally get the answer or the problem is resolved.

Our style is to continually call, push to completion and be gracious when something actually gets done. Threats or loss of patience won't move Argentines. They move at their own pace, and nothing is so important to them that it speeds up that pace.

In many ways, we feel as if we have arrived in Argentina and Mendoza at the best of moments. The wine industry has pumped $15 billion into the city alone in recent years, which has helped build a formidable infrastructure—including excellent and affordable health care.

With services for doctors and dentists about 20% of the cost in the U.S., many expats self-insure. (Tom recently had an old crown removed, the tooth pulled, and a bone graft and implant done—all for $600.)

Each year, tens of thousands of foreigners flock to Mendoza to visit the region's 1,200 wineries. The biggest annual event in the city is the Fiesta Nacional de la Vendimia (the National Wine Harvest Festival) in early March. A week of concerts and parades culminate in the festival queen's coronation in the San Martin Park Amphitheater.

In all, we are very thankful that we found Mendoza, and that this lovely Argentine city has graciously embraced us. We envision a future where we will sit on the veranda of our "estancia" (farm or ranch house), sipping one of our Malbec wines, looking out at our vineyard and saying: "This is la vida buena."

Saturday, December 18, 2010

wine's carbon footprint

[from Pascale Bonnefoy at NPR, December 17, 2010]

How Green Is Your Glass Of Merlot?

Vineyards, like Montgras in Santa Cruz, Chile, are beginning to figure out how much fine wines contribute to climate change.

In Chile, the path from vine to wine is easy to trace: Grapes are grown, harvested, fermented and then bottled and shipped around the world.

The environmental cost of that undertaking is harder to measure. But Chilean winemakers have little choice than to embrace the challenge.

If they don’t, there could be no place for their merlots and cabernets on international shelves.

Major retail stores and governments want to know just how much fine wines contribute to climate change. And they want consumers to know too.

That means offering a calculation of just how much greenhouse gas is emitted per glass of wine.

Chile was the fifth-largest wine exporter in the world last year and is rapidly expanding. The United States and the United Kingdom are by far the main destinations for its wine, followed by the Netherlands, Canada, Brazil and Japan.

In 2012, the European Union will require all products to carry eco-labels, and next year France will attempt a yearlong trial with carbon footprint labeling. Japan is also experimenting with a carbon footprint label for dozens of beverage and food companies.

In December 2007, the government export promotion agency ProChile saw a story from the BBC urging consumers not to buy Chilean cherries because they come from far away and contain a great deal of CO2. That sounded the alarm that Chilean exporters needed to start paying attention to this issue, said Paola Conca, head of the Sustainable Trade Department at ProChile.

And Chilean wine producers are now onboard, working to measure the carbon footprint of their operations and reduce, or offset, their emissions.

After doing measurements, they realized they needed to focus most of their efforts on the energy-intensive post-harvest stages. A study commissioned last year by the governmental Foundation for Agrarian Innovation found that bottling and storage were the biggest causes of emissions in the wine industry. Several vineyards also found that sea freight contributed significantly.

Chilean wine producers found that bottling and storage were the biggest causes of emissions in the wine industry.

So far no Chilean wine has yet to boast a carbon footprint label, but many vineyards have been certified carbon neutral, meaning they have offset their greenhouse gas emissions by investing in sustainable energy projects around the world.

Vina De Martino, one of Chile's leading organic wine producers, measured all of its carbon emissions in 2007. Two years later, it launched the first carbon-neutral wine in Latin America and became the first carbon-neutral winery in South America. It reduced its emissions by building a wastewater treatment plant and by buying carbon credits.

Cono Sur, also an organic producer, invested in waste gas power in Germany and wind power plants in Turkey and India to compensate for its greenhouse gas emissions during product delivery.

As Chilean wine companies examine their environmental impact, they're realizing the most urgent target is energy efficiency.

Vina Errazuriz, for instance, built two storage facilities with skylights and large windows to save energy; one of them has a geothermal warming system. Vina Los Vascos installed thermosolar panels and Solatubes on the ceiling of its storage rooms, saving 50 percent of energy costs during the winter and 100 percent during the rest of the year.

And many vineyards, like De Martino, Emiliana, Cono Sur and Concho y Toro — Chile’s main wine producer and exporter — have switched to lighter bottles that use recycled glass and labels.

"It isn't cheap, but it's an investment priority. It will be ultimately compensated, because consumers, especially in Europe, care about which producers are neutral or are working to reduce their emissions," said Alejandra Lapostol, head of the sustainable development committee at Cono Sur.

"The industry is fully aware that if we don't measure our carbon footprint and do not shift to sustainable production, we aren't going to be able to sell our wines," she said.

But Chile is facing a predicament that is beyond the control of any exporter: A considerable proportion of the country's energy sources are heavy contaminants. About 18 percent of the country's energy comes from oil and about 9 percent from coal, and those numbers are only trending upward. From 2000 to 2010, the use of geothermal energy rose about 15 percent, at the expense of hydroelectricity.

Moreover, a controversial thermoelectric plant project, now in the last stages of environmental assessment, will practically double the amount of coal-based energy in the future. The coal- and petcoke-based Castilla plant to be built about 500 miles north of the capital will supply energy to two-thirds of the country, right through wine-producing lands, weighing on the carbon footprint of every bottle produced.

"It's easy to talk about diversifying energy sources, but renewable energies are expensive. So the country has to decide: Do we want to produce with a lower carbon footprint or do we want products that are more price-competitive?" asked Rodrigo Valenzuela, who consults for nearly 10 Chilean vineyards and works for the consulting firm Deuman, which specializes in climate change and energy.

Major supermarkets and retail stores around the world, such as Tesco in the U.K., Casino in France and Wal-Mart in the United States, are already using voluntary carbon-labeling schemes, pressuring suppliers to adopt more sustainable production practices.

"Wal-Mart is saying that if their suppliers are not sustainable, they won't place their products on their shelves. Wal-Mart has pledged to diminish its emissions and to achieve it, has to make its suppliers do the same,” said Lapostol.

Chilean wine producers know they need to invest more, and "Innovate or Die" seems to be their motto.

"We need to be proactive and not wait for these regulations to be mandatory and turn into market barriers," said Juan Somavia, managing director of Wines of Chile, an industry association representing about 95 percent of producers. "When these demands come into effect, we are going to be prepared."

How Green Is Your Glass Of Merlot?

Vineyards, like Montgras in Santa Cruz, Chile, are beginning to figure out how much fine wines contribute to climate change.

In Chile, the path from vine to wine is easy to trace: Grapes are grown, harvested, fermented and then bottled and shipped around the world.

The environmental cost of that undertaking is harder to measure. But Chilean winemakers have little choice than to embrace the challenge.

If they don’t, there could be no place for their merlots and cabernets on international shelves.

Major retail stores and governments want to know just how much fine wines contribute to climate change. And they want consumers to know too.

That means offering a calculation of just how much greenhouse gas is emitted per glass of wine.

Chile was the fifth-largest wine exporter in the world last year and is rapidly expanding. The United States and the United Kingdom are by far the main destinations for its wine, followed by the Netherlands, Canada, Brazil and Japan.

In 2012, the European Union will require all products to carry eco-labels, and next year France will attempt a yearlong trial with carbon footprint labeling. Japan is also experimenting with a carbon footprint label for dozens of beverage and food companies.

In December 2007, the government export promotion agency ProChile saw a story from the BBC urging consumers not to buy Chilean cherries because they come from far away and contain a great deal of CO2. That sounded the alarm that Chilean exporters needed to start paying attention to this issue, said Paola Conca, head of the Sustainable Trade Department at ProChile.

And Chilean wine producers are now onboard, working to measure the carbon footprint of their operations and reduce, or offset, their emissions.

After doing measurements, they realized they needed to focus most of their efforts on the energy-intensive post-harvest stages. A study commissioned last year by the governmental Foundation for Agrarian Innovation found that bottling and storage were the biggest causes of emissions in the wine industry. Several vineyards also found that sea freight contributed significantly.

Chilean wine producers found that bottling and storage were the biggest causes of emissions in the wine industry.

So far no Chilean wine has yet to boast a carbon footprint label, but many vineyards have been certified carbon neutral, meaning they have offset their greenhouse gas emissions by investing in sustainable energy projects around the world.

Vina De Martino, one of Chile's leading organic wine producers, measured all of its carbon emissions in 2007. Two years later, it launched the first carbon-neutral wine in Latin America and became the first carbon-neutral winery in South America. It reduced its emissions by building a wastewater treatment plant and by buying carbon credits.

Cono Sur, also an organic producer, invested in waste gas power in Germany and wind power plants in Turkey and India to compensate for its greenhouse gas emissions during product delivery.

As Chilean wine companies examine their environmental impact, they're realizing the most urgent target is energy efficiency.

Vina Errazuriz, for instance, built two storage facilities with skylights and large windows to save energy; one of them has a geothermal warming system. Vina Los Vascos installed thermosolar panels and Solatubes on the ceiling of its storage rooms, saving 50 percent of energy costs during the winter and 100 percent during the rest of the year.

And many vineyards, like De Martino, Emiliana, Cono Sur and Concho y Toro — Chile’s main wine producer and exporter — have switched to lighter bottles that use recycled glass and labels.

"It isn't cheap, but it's an investment priority. It will be ultimately compensated, because consumers, especially in Europe, care about which producers are neutral or are working to reduce their emissions," said Alejandra Lapostol, head of the sustainable development committee at Cono Sur.

"The industry is fully aware that if we don't measure our carbon footprint and do not shift to sustainable production, we aren't going to be able to sell our wines," she said.

But Chile is facing a predicament that is beyond the control of any exporter: A considerable proportion of the country's energy sources are heavy contaminants. About 18 percent of the country's energy comes from oil and about 9 percent from coal, and those numbers are only trending upward. From 2000 to 2010, the use of geothermal energy rose about 15 percent, at the expense of hydroelectricity.

Moreover, a controversial thermoelectric plant project, now in the last stages of environmental assessment, will practically double the amount of coal-based energy in the future. The coal- and petcoke-based Castilla plant to be built about 500 miles north of the capital will supply energy to two-thirds of the country, right through wine-producing lands, weighing on the carbon footprint of every bottle produced.

"It's easy to talk about diversifying energy sources, but renewable energies are expensive. So the country has to decide: Do we want to produce with a lower carbon footprint or do we want products that are more price-competitive?" asked Rodrigo Valenzuela, who consults for nearly 10 Chilean vineyards and works for the consulting firm Deuman, which specializes in climate change and energy.

Major supermarkets and retail stores around the world, such as Tesco in the U.K., Casino in France and Wal-Mart in the United States, are already using voluntary carbon-labeling schemes, pressuring suppliers to adopt more sustainable production practices.

"Wal-Mart is saying that if their suppliers are not sustainable, they won't place their products on their shelves. Wal-Mart has pledged to diminish its emissions and to achieve it, has to make its suppliers do the same,” said Lapostol.

Chilean wine producers know they need to invest more, and "Innovate or Die" seems to be their motto.

"We need to be proactive and not wait for these regulations to be mandatory and turn into market barriers," said Juan Somavia, managing director of Wines of Chile, an industry association representing about 95 percent of producers. "When these demands come into effect, we are going to be prepared."

Monday, November 22, 2010

Osvaldo Domingo, Cafayate winemaker

[from El Tribuno, Salta, 11/21/10]

Good interview/article about Juan "Palo" Domingo, a Cafayate winemaker. I hope to translate it soon.

DICE LO SUYO/ JUAN "PALO" DOMINGO

“Cafayate es la reina de Salta”

Por FLAVIO PALACIOS, El tribuno

Domingo 21 de Noviembre de 2010 Salta

El conocido y muy respetado empresario vitivinícola vallisto Osvaldo Domingo se prestó a una charla en exclusiva con El Tribuno en la que desgranó su historia de vida mechada con numerosas anécdotas y definiciones fuertes sobre la realidad productiva y política de Cafayate y la provincia.