[from Suzanne Jill Levine's Manuel Puig and the Spider Woman: His Life and Fictions, Farrar Straus and Giroux, 2000]

. . . the nightmare atmosphere of the mid-seventies, when military officials exploited their power as rapists and torturers of their victims but also used female captives, usually "Montoneras" (left-wing Peronist guerrillas), as cultivated geishas. Instead of dining at home with their wives, who were the uneducated daughters of other officers, the officers would take these highly literate ex-citizens out to dinner, to "discuss books, movies, politics."

Showing posts with label history. Show all posts

Showing posts with label history. Show all posts

Sunday, June 26, 2011

Saturday, June 4, 2011

the origin of the tango

[from Suzanne Jill Levine's biography of Manuel Puig: Manuel Puig and the Spider Woman, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000]

Tangos spoke of "poor spinsters" who had been left in the dust because women (unlike men) gave "everything" when they loved; of men who had been abandoned by their women; and, ultimately, of the burden of being a man. Pitched in the nasal, whining tones of Libertad Lamarque or Carlos Gardel, tangos were not exotic, like their exported image, but as homespun tangos originated in the 1890s as a lascivious dance in the brothels of Buenos Aires, in the dockside tenements teeming with new immigrants from Italy, Spain, and Eastern Europe. Of remote African origin, and in its original form a duel of sexuality and violence, domination and submission, it showed (as Borges put it) that "a fight could be a celebration." At first its lyrics were improvised and obscene, and then they began to tell rustic sentimental stories about gauchos and their women. Finally, the lonely, seamy side of the life and love became its main subject, tinged almost always with bitter recrimination.

A reflection of the "half breed" culture of Argentina, by the twenties the tango was popularized beyond the banks of the Boca by slick-haired idol Carlos Gardel, the illegitimate son of a French prostitute. He had begun his singing career in the house where his mother worked, where whores and hoodlums would bump and grind, thigh against pelvis, "cutting" or pausing suggestively; in the brothels men also danced with men, crossing the line between machismo and buggery, and women danced with women, to excite their clients but also because many prostitutes were, or became, lesbians. Just as the forbidden waltz at first caused a scandal in Johann Strauss's Vienna, so the lumpen tango, straight from the lower depths inhabited by harlots, thieves, and foreigners, was too lewd for polite criollo society, where it struck both a xenophobic and homophobic nerve. Many prostitutes were Jewish, sold into white slavery from Eastern Europe; the petty thieves or lunfardos were often Italian. After 1910 the National Council of Education (presided over by educator Ramos Mejía) "nationalized" the tango, or cleansed it of its associations with Jews and homosexuals. The tango was tied up in a nostalgia for its own past, not only for its former festivity but for "homosexual desire lost in the sanitization of a forbidden dance." Only after it was adopted by the sophisticated "gay Paris" of the "lost generation" between the wars did this racy rite of arousal gain legitimate cachet. But it lost something in translation, now refined into a stylized ballroom dance for the elegant international set; or, in Borges's words, "a devilish orgy had become a way of walking." For the lower-class provincials in Argentina, however, the sizzling lyrics of seduction and abandonment remained their language of love.

Gardel was an Argentine hero . . . a talented musician and a bisexual celebrity who necessarily cast a veil of discretion over his private life; a man of modest origins, known to be kind and generous, a true man of the people. Gardel not only sang but composed, and his lyricist was Alfred LePera . . . So as not to disillusion his fans all over South America and in Europe, it was never disclosed that Gardel and LePera were probably lovers. The duo died together, on tour, in a plane crash over Medellin, Colombia, in 1937; it was a national tragedy. Manuel [Puig] would one day write a musical in honor of this universally mourned Argentine tango star who lived a double life. Called Gardel, uma Lembrança (Remembering Gardel), it depicted the life of a man whose "universe is inhabited by defeated creatures, forgiven betrayals, and the idealism of one's first love. Resentments do not last in his world because he understands and empathizes with all people. He never looks down upon them but rather sees them as equals."

Many thanks to Peter E., who writes:

I'm surprised that you did not report that Rudolph Valentino introduced the tango to American audiences in 1921 in his movie, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, from the Argentine novel [eponymous, authored by Vicente Blasco Ibáñez]. I have seen it. I recommend it.

|

| Libertad Lamarque |

Tangos spoke of "poor spinsters" who had been left in the dust because women (unlike men) gave "everything" when they loved; of men who had been abandoned by their women; and, ultimately, of the burden of being a man. Pitched in the nasal, whining tones of Libertad Lamarque or Carlos Gardel, tangos were not exotic, like their exported image, but as homespun tangos originated in the 1890s as a lascivious dance in the brothels of Buenos Aires, in the dockside tenements teeming with new immigrants from Italy, Spain, and Eastern Europe. Of remote African origin, and in its original form a duel of sexuality and violence, domination and submission, it showed (as Borges put it) that "a fight could be a celebration." At first its lyrics were improvised and obscene, and then they began to tell rustic sentimental stories about gauchos and their women. Finally, the lonely, seamy side of the life and love became its main subject, tinged almost always with bitter recrimination.

|

| Carlos Gardel |

A reflection of the "half breed" culture of Argentina, by the twenties the tango was popularized beyond the banks of the Boca by slick-haired idol Carlos Gardel, the illegitimate son of a French prostitute. He had begun his singing career in the house where his mother worked, where whores and hoodlums would bump and grind, thigh against pelvis, "cutting" or pausing suggestively; in the brothels men also danced with men, crossing the line between machismo and buggery, and women danced with women, to excite their clients but also because many prostitutes were, or became, lesbians. Just as the forbidden waltz at first caused a scandal in Johann Strauss's Vienna, so the lumpen tango, straight from the lower depths inhabited by harlots, thieves, and foreigners, was too lewd for polite criollo society, where it struck both a xenophobic and homophobic nerve. Many prostitutes were Jewish, sold into white slavery from Eastern Europe; the petty thieves or lunfardos were often Italian. After 1910 the National Council of Education (presided over by educator Ramos Mejía) "nationalized" the tango, or cleansed it of its associations with Jews and homosexuals. The tango was tied up in a nostalgia for its own past, not only for its former festivity but for "homosexual desire lost in the sanitization of a forbidden dance." Only after it was adopted by the sophisticated "gay Paris" of the "lost generation" between the wars did this racy rite of arousal gain legitimate cachet. But it lost something in translation, now refined into a stylized ballroom dance for the elegant international set; or, in Borges's words, "a devilish orgy had become a way of walking." For the lower-class provincials in Argentina, however, the sizzling lyrics of seduction and abandonment remained their language of love.

|

| Carlos Gardel y Alfred LePera |

Gardel was an Argentine hero . . . a talented musician and a bisexual celebrity who necessarily cast a veil of discretion over his private life; a man of modest origins, known to be kind and generous, a true man of the people. Gardel not only sang but composed, and his lyricist was Alfred LePera . . . So as not to disillusion his fans all over South America and in Europe, it was never disclosed that Gardel and LePera were probably lovers. The duo died together, on tour, in a plane crash over Medellin, Colombia, in 1937; it was a national tragedy. Manuel [Puig] would one day write a musical in honor of this universally mourned Argentine tango star who lived a double life. Called Gardel, uma Lembrança (Remembering Gardel), it depicted the life of a man whose "universe is inhabited by defeated creatures, forgiven betrayals, and the idealism of one's first love. Resentments do not last in his world because he understands and empathizes with all people. He never looks down upon them but rather sees them as equals."

Many thanks to Peter E., who writes:

I'm surprised that you did not report that Rudolph Valentino introduced the tango to American audiences in 1921 in his movie, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, from the Argentine novel [eponymous, authored by Vicente Blasco Ibáñez]. I have seen it. I recommend it.

Wednesday, June 1, 2011

Argentine President Menem: 1989-1999

[from Luis Alberto Romero's A History of Argentina in the Twentieth Century, tr. James P. Brennan, Pennsylvania State, 1994]

[I highly recommend this book. Naturally, Romero (the author) infuses the work with his own political opinions, & since I don't know much of this history from any other source, I don't (yet) have a contrasting point of view. Still, I learned a lot. It's available as an ebook.]

Menem combined discretion with a style of governing more suited to a monarch than the chief of state of a republic. To judge by those who knew him intimately, Menem concentrated on politics but was not terribly interested in policy matters. He offered broad objectives and delegated to his collaborators the specific details, which bored. him. Thus he is remembered as listening to the explanation for some important matter while he watched a soccer match or flipped through the channels of his television. Moreover, he continued to enjoy a playboy's lifestyle despite being married. For his nocturnal endeavors, he generally used a suite in the luxurious Alvear Palace, whose owner was one of the members of his intimate circle. Menem relished flouting convention and even the law; he drove a Ferrari sports car that he had received as a presidential gift, for reasons that were never made clear, at high speeds and traveled in two hours from Buenos Aires to the seaside resort of Pinamar and at similar speeds to other beach resorts for an occasional wild weekend. After his public separation from his wife, Zulema Yoma, whom he had evicted by force from the presidential retreat in Olivos, he became somewhat more sedentary and transformed the presidential residence into a veritable court, with its own golf course and private golf instructor, zoo, valet, physician, hair stylist, "court jester," and a select group of courtesans, comrades during his nights of insomnia and witnesses to his recurring bouts of depression. Like a medieval prince, he often trotted the globe with his retinue aboard a presidential airplane worthy of a monarch. . . .

Among the original fideles, there mingled provincial politicians, union leaders, former Montoneros now transformed into neoliberals, extreme right-wing groups, ex-collaborators of Admiral Massera, and other fauna that he had collected throughout his political career. Soon others joined him, recruited among his defeated rivals, the renovadores. Loyalty was rewarded with protection and impunity as far as possible.

In addition, the chief executive was the caretaker of the spoils of office, which he distributed generously. Such had always been the true sign of authority in political leadership in Argentina, and Menem refined the practice. Corruption was widely employed to wear down resistance and coopt adversaries by sealing a pact among the members of the governing circle as powerful as the blood pact that united the military under the dictatorship. Corruption was practiced in an ostentatious fashion. "Nobody makes money by working," the trade-union official Luis Barrionuevo declared, before proposing as a solution to the country's troubles that "everyone stop stealing for two years."

[I highly recommend this book. Naturally, Romero (the author) infuses the work with his own political opinions, & since I don't know much of this history from any other source, I don't (yet) have a contrasting point of view. Still, I learned a lot. It's available as an ebook.]

|

| President Carlos Saúl Menem |

Menem combined discretion with a style of governing more suited to a monarch than the chief of state of a republic. To judge by those who knew him intimately, Menem concentrated on politics but was not terribly interested in policy matters. He offered broad objectives and delegated to his collaborators the specific details, which bored. him. Thus he is remembered as listening to the explanation for some important matter while he watched a soccer match or flipped through the channels of his television. Moreover, he continued to enjoy a playboy's lifestyle despite being married. For his nocturnal endeavors, he generally used a suite in the luxurious Alvear Palace, whose owner was one of the members of his intimate circle. Menem relished flouting convention and even the law; he drove a Ferrari sports car that he had received as a presidential gift, for reasons that were never made clear, at high speeds and traveled in two hours from Buenos Aires to the seaside resort of Pinamar and at similar speeds to other beach resorts for an occasional wild weekend. After his public separation from his wife, Zulema Yoma, whom he had evicted by force from the presidential retreat in Olivos, he became somewhat more sedentary and transformed the presidential residence into a veritable court, with its own golf course and private golf instructor, zoo, valet, physician, hair stylist, "court jester," and a select group of courtesans, comrades during his nights of insomnia and witnesses to his recurring bouts of depression. Like a medieval prince, he often trotted the globe with his retinue aboard a presidential airplane worthy of a monarch. . . .

Among the original fideles, there mingled provincial politicians, union leaders, former Montoneros now transformed into neoliberals, extreme right-wing groups, ex-collaborators of Admiral Massera, and other fauna that he had collected throughout his political career. Soon others joined him, recruited among his defeated rivals, the renovadores. Loyalty was rewarded with protection and impunity as far as possible.

In addition, the chief executive was the caretaker of the spoils of office, which he distributed generously. Such had always been the true sign of authority in political leadership in Argentina, and Menem refined the practice. Corruption was widely employed to wear down resistance and coopt adversaries by sealing a pact among the members of the governing circle as powerful as the blood pact that united the military under the dictatorship. Corruption was practiced in an ostentatious fashion. "Nobody makes money by working," the trade-union official Luis Barrionuevo declared, before proposing as a solution to the country's troubles that "everyone stop stealing for two years."

Monday, May 30, 2011

"governing" Argentina: 1976-1983

[from Luis Alberto Romero's A History of Argentina in the Twentieth Century, tr. James P. Brennan, Pennsylvania State, 1994]

The so-called Process of National Reorganization, or the Process as it was simply called, entailed the coexistence of a clandestine terrorist state in charge of repression and another visible one, subject to the norms established by the military government itself but submitting its actions to a certain legal scrutiny. In practice, this distinction was not maintained, and the ilegal clandestine state was corroding, corrupting the state institutions in their entirety and the state's very juridical foundations.

The first ambiguity was found precisely where power resided. Despite the fact that a strong executive was an Argentine tradition and that the unity of command was always one of the principles of the armed forces, the authority of the president – who in the beginning was a first among equals and then not even that – turned out to be weak and subject to permanent scrutiny, with restraints imposed by the commanders of the three services. The Statute of the Process and the subsequent complementary government decrees – which shut down the congress, purged the judicial system, and prohibited political activity – created the Military Junta, with power to designate the president and control many of his actions. The problem was that no one's powers were clearly delineated but were rather the result of the changing balance of forces. A newly created Advisory Legislative Commission, made up of three representatives of each branch subordinate to the orders of their commanders, was another instance of alliances and confrontations. To top it off, every executive position, from governors to mayors, as well as the administration of state companies and other government agencies, was divided among the armed forces. Those who occupied these positions thus depended on a double chain of command: that of the state and that of their service branch. This amounted to a feudalized anarchy rather than a state made cohesive and constituted through executive power.

The same anarchy existed with respect to the legal norms that the government provided itself. There was confusion about the very nature of these norms – laws, decrees, and state regulations being jumbled together without criteria – as well as who had the power to declare them and what was the full extent of their powers. There was also a well-known reluctance to discuss the reason for such norms; even their very existence was on occasion a secret. The military government preferred omnibus laws and frequently granted itself broad discretionary powers, but also tolerated the repeated violation or only partial fulfillment of its own legislation. Contaminated by the clandestine terrorist state, the country's entire juridical structure was similarly affected, to the point that there were practically no legal limits on the exercise of power, which functioned as the discretionary power of the state. This corruption of purpose was extended to public administration, where the most able personnel were removed. Arbitrary decisions were made by minor bureaucrats, transformed into little dictators without control and lacking the ability to assert control themselves. . . .

Fragmentation of power, centrifugal tendencies, and anarchy were the product of the strict division of power among the three armed service branches, to the point that there was no means of requesting a final appeal to authority that might arbitrate in the event of conflicts between the branches. But such a state of affairs was also the result of the existence of clear factions in the army, where from the repression emerged true warlords, generals Videla and Roberto Viola – Videla's second-in-command in the army – the most powerful factions were established, but even these were far from dominant.

These commanders backed Martínez de Hoz – a figure criticized by the more nationalist military officers, who abounded in the ranks of younger officers – but they recognized the necessity of finding some political solution in the future. They maintained communication with the leadership of the political parties, who hoped that this group represented the most reasonable and even the most progressive sector of the military, perhaps because it was the faction that recognized the need to control the repression in some way.

Other groups, whose most prominent figures were the generals Luciano Benjamín Menéndez and Carlos Suárez Mason, commanders of the army's Third Corps and First Corps with their headquarters in Córdoba and Buenos Aires, respectively, and the chief of police of Buenos Aires province, General Ramón J. Camps, a key figure in the repression, maintained that the dictatorship should continue sine die and that the repression – which these figures carried out with special savagery – should be taken to its final consequences. . . .

The third group in the military was that of the navy, firmly led by its commander, Admiral Emilio Eduardo Massera, who, trusting in his own political talents, proposed to find a political agreement that would popularly legitimize the Process and at the same time carry him to power. Massera, who carried out a major part of the repression from the navy mechanics' school and gained distinction in that sinister competition, always played his own game. He harried Videla to limit his power and distanced himself from Martínez de Hoz. He took great pains to find issues and causes that would win some degree of popular support for the government . . . When he retired, Massera established a political think tank, his own newspaper, an international publicity agency based in Paris, a political party – Social Democracy – and a bizarre personal staff made up of former members of the guerrilla organizations kidnapped and imprisoned in the navy mechanics' school, who agreed to collaborate in the admiral's political projects. . . .

In summary, the politics of order began to fail among the armed forces themselves, because the military behaved in an undisciplined and factional manner and did little to maintain the order that it sought to impost on society. Nevertheless, for five years, the military managed to secure a relative peace, a peace of the tomb, owing to society's scant ability to respond, partly because it had been battered or threatened by the repression and partly because it was disposed to tolerate a great deal from a government that, after the preceding chaos, had promised a minimum order.

The so-called Process of National Reorganization, or the Process as it was simply called, entailed the coexistence of a clandestine terrorist state in charge of repression and another visible one, subject to the norms established by the military government itself but submitting its actions to a certain legal scrutiny. In practice, this distinction was not maintained, and the ilegal clandestine state was corroding, corrupting the state institutions in their entirety and the state's very juridical foundations.

|

| Admiral Emilio Eduardo Massera, General Jorge Rafael Videla, & Air Force Brigadier Orlando Ramón Agosti |

The first ambiguity was found precisely where power resided. Despite the fact that a strong executive was an Argentine tradition and that the unity of command was always one of the principles of the armed forces, the authority of the president – who in the beginning was a first among equals and then not even that – turned out to be weak and subject to permanent scrutiny, with restraints imposed by the commanders of the three services. The Statute of the Process and the subsequent complementary government decrees – which shut down the congress, purged the judicial system, and prohibited political activity – created the Military Junta, with power to designate the president and control many of his actions. The problem was that no one's powers were clearly delineated but were rather the result of the changing balance of forces. A newly created Advisory Legislative Commission, made up of three representatives of each branch subordinate to the orders of their commanders, was another instance of alliances and confrontations. To top it off, every executive position, from governors to mayors, as well as the administration of state companies and other government agencies, was divided among the armed forces. Those who occupied these positions thus depended on a double chain of command: that of the state and that of their service branch. This amounted to a feudalized anarchy rather than a state made cohesive and constituted through executive power.

The same anarchy existed with respect to the legal norms that the government provided itself. There was confusion about the very nature of these norms – laws, decrees, and state regulations being jumbled together without criteria – as well as who had the power to declare them and what was the full extent of their powers. There was also a well-known reluctance to discuss the reason for such norms; even their very existence was on occasion a secret. The military government preferred omnibus laws and frequently granted itself broad discretionary powers, but also tolerated the repeated violation or only partial fulfillment of its own legislation. Contaminated by the clandestine terrorist state, the country's entire juridical structure was similarly affected, to the point that there were practically no legal limits on the exercise of power, which functioned as the discretionary power of the state. This corruption of purpose was extended to public administration, where the most able personnel were removed. Arbitrary decisions were made by minor bureaucrats, transformed into little dictators without control and lacking the ability to assert control themselves. . . .

|

| General Roberto Viola |

Fragmentation of power, centrifugal tendencies, and anarchy were the product of the strict division of power among the three armed service branches, to the point that there was no means of requesting a final appeal to authority that might arbitrate in the event of conflicts between the branches. But such a state of affairs was also the result of the existence of clear factions in the army, where from the repression emerged true warlords, generals Videla and Roberto Viola – Videla's second-in-command in the army – the most powerful factions were established, but even these were far from dominant.

|

| Minister of Economy José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz |

These commanders backed Martínez de Hoz – a figure criticized by the more nationalist military officers, who abounded in the ranks of younger officers – but they recognized the necessity of finding some political solution in the future. They maintained communication with the leadership of the political parties, who hoped that this group represented the most reasonable and even the most progressive sector of the military, perhaps because it was the faction that recognized the need to control the repression in some way.

|

| General Ramón J. Camps |

Other groups, whose most prominent figures were the generals Luciano Benjamín Menéndez and Carlos Suárez Mason, commanders of the army's Third Corps and First Corps with their headquarters in Córdoba and Buenos Aires, respectively, and the chief of police of Buenos Aires province, General Ramón J. Camps, a key figure in the repression, maintained that the dictatorship should continue sine die and that the repression – which these figures carried out with special savagery – should be taken to its final consequences. . . .

|

| Admiral Emilio Eduardo Massera |

The third group in the military was that of the navy, firmly led by its commander, Admiral Emilio Eduardo Massera, who, trusting in his own political talents, proposed to find a political agreement that would popularly legitimize the Process and at the same time carry him to power. Massera, who carried out a major part of the repression from the navy mechanics' school and gained distinction in that sinister competition, always played his own game. He harried Videla to limit his power and distanced himself from Martínez de Hoz. He took great pains to find issues and causes that would win some degree of popular support for the government . . . When he retired, Massera established a political think tank, his own newspaper, an international publicity agency based in Paris, a political party – Social Democracy – and a bizarre personal staff made up of former members of the guerrilla organizations kidnapped and imprisoned in the navy mechanics' school, who agreed to collaborate in the admiral's political projects. . . .

In summary, the politics of order began to fail among the armed forces themselves, because the military behaved in an undisciplined and factional manner and did little to maintain the order that it sought to impost on society. Nevertheless, for five years, the military managed to secure a relative peace, a peace of the tomb, owing to society's scant ability to respond, partly because it had been battered or threatened by the repression and partly because it was disposed to tolerate a great deal from a government that, after the preceding chaos, had promised a minimum order.

Thursday, May 26, 2011

"the state decisively intervened"

[from Luis Alberto Romero's A History of Argentina in the Twentieth Century, tr. James P. Brennan, Pennsylvania State, 1994]

As in Peronist Argentina, in the United States and Europe the state decisively intervened, presiding over economic reconstruction and mediating complex agreements between business and labor. But this increasing power of the state – of the interventionist and welfare state – was accompanied by an integration and liberalization of economic relations in the capitalist world.

In 1947, the Bretton Woods monetary agreements established the dollar as the global currency, and capital began to move freely again in the world. Those countries shut off from the outside world grew fewer in number, and multinationals began to establish themselves in markets that had previously been prohibited. For the countries whose economies had grown based on the internal market and in carefully protected fashion, as in the case of the Latin American, particularly Argentine, economy, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – a financial entity that had enormous power in the new context – proposed so-called orthodox policies: stabilizing the currency by abandoning unrestrained monetary emission, ceasing to subsidize "artificial" sectors, opening markets, and stimulating traditional export activities

Nevertheless, an alternative policy gradually began to be formulated, elaborated especially bh the United Nations' Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLA). ECLA proposed that the "developed" countries help the "undeveloped" ones to eliminate the factors responsible for their backwardness through appropriate investments in key sectors, accompanied by "structural" reforms, such as agrarian reform. From that point on, the "monetary" and "structuralist" remedies competed in public opinion and as government policies. It might be thought that both strategies were in the end complementary, but for the time being they had different political representations; whereas the first led to revitalizing the old foreign economic partners, oligarchic sectors, and perhaps dictatorship, the second compelled deep changes: modernization of society that would be crowned by the establishment of stable democracies, similar to those of the developed countries.

To adapt itself to this world of reconstituted capitalism, liberalism, and democracy, it was not enough to restore constitutional order to Argentina and put an end to the vestiges of a regine inspired by the authoritarian governments of the interwar years. It was necessary to modernize and make adjustments in the economy, to transform the productive apparatus. After 1955, proposals to open up the economy and to modernize were shared values in Argentina. But the methods to be used for this transformation generated deep disputes between those who trusted foreign capital and those, from the nationalist tradition that had nourished Peronism or from the anti-imperialist left, who were distrustful of it. The debates, which dominated two subsequent decades, revolved around how either to attract or to control foreign capital. Some local business sectors discovered the advantages of an association with foreign capital, but others that had grown and consolidated themselves under state protection felt they were certain victims, either from competition or from the ending of protection. These firms sought to hinder growth of foreign capital, and they found a welcome reception not only among nationalists and the left, but also among the majority of political parties.

Businesspeople, domestic or foreign, agreed that any modernization needed to alter the status achieved by the workers under Peronism. As it already had indicated at the end of the Peronist regime, business sought to reduce the workers' share of national income and also to increase productivity, rationalizing jobs and reducing the size of the labor force. These aims entailed curtailing the power of the unions and also the power that the workers, protected by legislation, had achieved on the shop floor. Cutting back wages and recovering management's authority in the workplace were the principal objectives in a general sentiment running against the status of greater equality achieved by the workers and the peculiar practice of citizenship on which Peronism had been based. Demands for a certain business rationalization combined with resentments that were difficult to admit but were undoubtedly strong among those who had made common cause against Perón.

Here was the greatest obstacle. As Juan Carlos Torre noted, at issue was a now-mature working class, well defended in a labor market, approaching near full employment, homogenous, and with a clear social and political identify.

As in Peronist Argentina, in the United States and Europe the state decisively intervened, presiding over economic reconstruction and mediating complex agreements between business and labor. But this increasing power of the state – of the interventionist and welfare state – was accompanied by an integration and liberalization of economic relations in the capitalist world.

In 1947, the Bretton Woods monetary agreements established the dollar as the global currency, and capital began to move freely again in the world. Those countries shut off from the outside world grew fewer in number, and multinationals began to establish themselves in markets that had previously been prohibited. For the countries whose economies had grown based on the internal market and in carefully protected fashion, as in the case of the Latin American, particularly Argentine, economy, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – a financial entity that had enormous power in the new context – proposed so-called orthodox policies: stabilizing the currency by abandoning unrestrained monetary emission, ceasing to subsidize "artificial" sectors, opening markets, and stimulating traditional export activities

Nevertheless, an alternative policy gradually began to be formulated, elaborated especially bh the United Nations' Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLA). ECLA proposed that the "developed" countries help the "undeveloped" ones to eliminate the factors responsible for their backwardness through appropriate investments in key sectors, accompanied by "structural" reforms, such as agrarian reform. From that point on, the "monetary" and "structuralist" remedies competed in public opinion and as government policies. It might be thought that both strategies were in the end complementary, but for the time being they had different political representations; whereas the first led to revitalizing the old foreign economic partners, oligarchic sectors, and perhaps dictatorship, the second compelled deep changes: modernization of society that would be crowned by the establishment of stable democracies, similar to those of the developed countries.

To adapt itself to this world of reconstituted capitalism, liberalism, and democracy, it was not enough to restore constitutional order to Argentina and put an end to the vestiges of a regine inspired by the authoritarian governments of the interwar years. It was necessary to modernize and make adjustments in the economy, to transform the productive apparatus. After 1955, proposals to open up the economy and to modernize were shared values in Argentina. But the methods to be used for this transformation generated deep disputes between those who trusted foreign capital and those, from the nationalist tradition that had nourished Peronism or from the anti-imperialist left, who were distrustful of it. The debates, which dominated two subsequent decades, revolved around how either to attract or to control foreign capital. Some local business sectors discovered the advantages of an association with foreign capital, but others that had grown and consolidated themselves under state protection felt they were certain victims, either from competition or from the ending of protection. These firms sought to hinder growth of foreign capital, and they found a welcome reception not only among nationalists and the left, but also among the majority of political parties.

Businesspeople, domestic or foreign, agreed that any modernization needed to alter the status achieved by the workers under Peronism. As it already had indicated at the end of the Peronist regime, business sought to reduce the workers' share of national income and also to increase productivity, rationalizing jobs and reducing the size of the labor force. These aims entailed curtailing the power of the unions and also the power that the workers, protected by legislation, had achieved on the shop floor. Cutting back wages and recovering management's authority in the workplace were the principal objectives in a general sentiment running against the status of greater equality achieved by the workers and the peculiar practice of citizenship on which Peronism had been based. Demands for a certain business rationalization combined with resentments that were difficult to admit but were undoubtedly strong among those who had made common cause against Perón.

Here was the greatest obstacle. As Juan Carlos Torre noted, at issue was a now-mature working class, well defended in a labor market, approaching near full employment, homogenous, and with a clear social and political identify.

Tuesday, May 24, 2011

20th century Argentina

[excerpts from Luis Alberto Romero's A History of Argentina in the Twentieth Century, tr. James P. Brennan, Pennsylvania State, 1994]

According to an 1884 law, education was to be secular, free, and mandatory. Replacing both the Catholic Church and immigrant associations, both of which had advanced greatly in this area, the state assumed all responsibility for education. Literacy ensured a basic education for everyone and at the same time the integration and nationalization of immigrants' children who, if in their homes they traced their past to some region of Italy or Spain, in school learned that the past dated from the founding fathers, Bernardino Rivadavia and Manuel Belgrano.

•

Hipólito Yrigoyen served as president from 1916 to 1922, the year that Marcelo T. deAlvear succeeded him in the presidency. In 1928, Yrigoyen was reelected, only to be deposed by a military revolt on September 6, 1930. It would be another sixty-one years before an elected president would peacefully transfer power to his successor. Thus, these twelve years in which democratic institutions began to function normally turned out to be an exceptional period in the long run.

•

The nationalists . . . finished fashioning their discourse . . . To the traditional criticisms of democracy were added a vigorous anti-Communism and an attack on liberalism, regarded as the root of all of society's evils. Typical for the period, they reduced all of their enemies to one: high finances and imperialism combined with the Communists, the foreigners responsible for national disintegration, and also the Jews, all united in a sinister conspiracy. They demanded the return to a hierarchical society such as had existed in the colonial period, uncontaminated by liberalism, organized by a corporatist state, and cemented by an integral Catholicism. . . . the nationalists demanded the establishment of a new governing elite that was national and not beholden to foreign interests. They believed they would find such an elite among the military.

•

Three important essays expressed profound intuitions about the "national soul" and set the tone for a broad collective reflection.

In 1931, Scalabrini Ortiz published The Man Who Is Alone and Waits: Scalabrini Ortiz's man of "Corrientes and Esmerelda" streets, who embodied the different traditions of an immigrant country and who was defined by his impulses, intuitions, and feelings. This "man" preferred his impulses to any ruminations or rational calculations and – reminiscent of Ortega y Gasset – constructed them with an image of himself and what he could become, which he judged more valuable than the social reality surrounding him.

For Eduardo Mallea, and amalgam was of doubtful worth. Mallea observed the crisis in the feeling of being Argentine, particularly among the elites, won over to comfortable living, idleness, and appearances, renouncing spirituality and more profound concerns about the nation's destiny. In his History of an Argentine Passion, published in 1935, Mallea contrasted that "visible Argentina" with another "invisible" one in which the new elites, at first hidden, were creating "an extreme exaltation of life."

Ezequiel Martínez Estrada was more radically pessimistic and saw the Argentine community as prisoner of a fatal destiny, with its origins in the Spanish conquest. In X-Ray of the Pampa, published in 1933, he noted the rift between the unruly masses, heirs to the resentment stemming from their status as mixed bloods, and certain Europhile elites incapable of understanding this society or of inculcating in it a system of norms and principles upheld by collective beliefs. These efforts to unmask the nature of "the Argentine soul," inquiring in ontological fashion into essential and singular qualities of Argentine society and culture, though reflecting common concerns throughout the Western world, were undoubtedly the intellectual expression of this new common restlessness to understand, defend, or construct "the national."

•

The military government that assumed power on June 4, 1943 . . . was initially headed by General Rawson, who resigned before being sworn in and was replaced by General Pedro Pablo Ramirez, a cabinet minister in the previous constitutional government. The episode is revealing of the multiple tendencies existing in the revolutionary group and of the uncertainty of the road they would follow, beyond the shared conviction that the constitutional order was finished and that the proclaimed candidacy of [Rubustiano] Patrón Costas [sugar magnate from Salta] would not fill the void in power. . . .

The military members of the government agreed on the necessity of silencing political unrest and social protest; the Communists were outlawed, the unions persecuted, and the CGT (General Confederation of Labor) – then divided into two factions – was interdicted. In addition, they disbanded Acción Argentina (Argentine Action), which included those who supported breaking off relations with the Axis. The government later did the same with the political parties, as well interdicting the universities, dismissing a vast number of professors who were members of the opposition, and eventually establishing obligatory religious instruction in the public schools. In these actions, the country's new military leaders counted on the collaboration of a cast of nationalists and Catholic integralists, some of them with a long-standing political involvement that went back to the Uriburu years, who set the tone for the military regime: authoritarian, antiliberal, messianic, obsessed with establishing a new social order, and avoiding the chaos of Communism that, they thought, was an inevitable consequence of the war. It was not difficult for the democratic opposition to identify the military government with Nazism. . . .

the trade agreement with Great Britain was maintained. The United States, on the other hand, attacked with increasing fury one of the only governments in the hemisphere reluctant to accompany its war effort against the Axis, one suspected of harboring Nazis. The State Department launched a crusade against the military government, unconcerned about the political consequences of its actions and ignoring conciliatory gestures on the part of Argentina. This campaign allowed the staunchest supporters of neutrality to gain ground, and the conflict thus unfolded at an escalating pace. . . .

for Argentina it was a matter of principle not to accept the diktat of the State Department. . . . In March 1945, with the end of the war at hand, Argentina accepted the U.S. demand – where a new leadership in the State Department promised better relations – and declared war against the Axis, the condition for being admitted to the United Nations, then in the process of being established.

•

In 1948, the Marshall Plan was launched, but the United States prohibited the dollars provided to Europe from being used for imports from Argentina. Then from 1949 onward as the European economies began to recover, the United States flooded markets with subsidized grains, and Argentina's participation declined drastically.

According to an 1884 law, education was to be secular, free, and mandatory. Replacing both the Catholic Church and immigrant associations, both of which had advanced greatly in this area, the state assumed all responsibility for education. Literacy ensured a basic education for everyone and at the same time the integration and nationalization of immigrants' children who, if in their homes they traced their past to some region of Italy or Spain, in school learned that the past dated from the founding fathers, Bernardino Rivadavia and Manuel Belgrano.

•

Hipólito Yrigoyen served as president from 1916 to 1922, the year that Marcelo T. deAlvear succeeded him in the presidency. In 1928, Yrigoyen was reelected, only to be deposed by a military revolt on September 6, 1930. It would be another sixty-one years before an elected president would peacefully transfer power to his successor. Thus, these twelve years in which democratic institutions began to function normally turned out to be an exceptional period in the long run.

•

The nationalists . . . finished fashioning their discourse . . . To the traditional criticisms of democracy were added a vigorous anti-Communism and an attack on liberalism, regarded as the root of all of society's evils. Typical for the period, they reduced all of their enemies to one: high finances and imperialism combined with the Communists, the foreigners responsible for national disintegration, and also the Jews, all united in a sinister conspiracy. They demanded the return to a hierarchical society such as had existed in the colonial period, uncontaminated by liberalism, organized by a corporatist state, and cemented by an integral Catholicism. . . . the nationalists demanded the establishment of a new governing elite that was national and not beholden to foreign interests. They believed they would find such an elite among the military.

•

Three important essays expressed profound intuitions about the "national soul" and set the tone for a broad collective reflection.

|

| Raúl Scalabrini Ortiz |

|

| Eduardo Mallea |

|

| Ezequiel Martínez Estrada |

•

The military government that assumed power on June 4, 1943 . . . was initially headed by General Rawson, who resigned before being sworn in and was replaced by General Pedro Pablo Ramirez, a cabinet minister in the previous constitutional government. The episode is revealing of the multiple tendencies existing in the revolutionary group and of the uncertainty of the road they would follow, beyond the shared conviction that the constitutional order was finished and that the proclaimed candidacy of [Rubustiano] Patrón Costas [sugar magnate from Salta] would not fill the void in power. . . .

The military members of the government agreed on the necessity of silencing political unrest and social protest; the Communists were outlawed, the unions persecuted, and the CGT (General Confederation of Labor) – then divided into two factions – was interdicted. In addition, they disbanded Acción Argentina (Argentine Action), which included those who supported breaking off relations with the Axis. The government later did the same with the political parties, as well interdicting the universities, dismissing a vast number of professors who were members of the opposition, and eventually establishing obligatory religious instruction in the public schools. In these actions, the country's new military leaders counted on the collaboration of a cast of nationalists and Catholic integralists, some of them with a long-standing political involvement that went back to the Uriburu years, who set the tone for the military regime: authoritarian, antiliberal, messianic, obsessed with establishing a new social order, and avoiding the chaos of Communism that, they thought, was an inevitable consequence of the war. It was not difficult for the democratic opposition to identify the military government with Nazism. . . .

the trade agreement with Great Britain was maintained. The United States, on the other hand, attacked with increasing fury one of the only governments in the hemisphere reluctant to accompany its war effort against the Axis, one suspected of harboring Nazis. The State Department launched a crusade against the military government, unconcerned about the political consequences of its actions and ignoring conciliatory gestures on the part of Argentina. This campaign allowed the staunchest supporters of neutrality to gain ground, and the conflict thus unfolded at an escalating pace. . . .

for Argentina it was a matter of principle not to accept the diktat of the State Department. . . . In March 1945, with the end of the war at hand, Argentina accepted the U.S. demand – where a new leadership in the State Department promised better relations – and declared war against the Axis, the condition for being admitted to the United Nations, then in the process of being established.

•

In 1948, the Marshall Plan was launched, but the United States prohibited the dollars provided to Europe from being used for imports from Argentina. Then from 1949 onward as the European economies began to recover, the United States flooded markets with subsidized grains, and Argentina's participation declined drastically.

Saturday, May 21, 2011

Argentina's military-industrial complex by the early 1980s

[from Daniel Poneman's Argentina: Democracy on Trial, Paragon, 1987; photos from FM's current website]

Not surprisingly, over the years the Argentina military has become an economic powerhouse, in land, labor, and capital. The army is one of the biggest landowners in Argentina. By 1983, there were 153,000 soldiers in uniform, and military spending comprised 12 percent of the national budget. Each branch of the armed forces owns or controls a domain of large state enterprises. The air force writ runs to aircraft production, the national airlines, air insurance, and travel agencies. The navy presides over a complex including a merchant fleet, shipyards, weapons research and production.

The army has the big kid on the block, drily denominated the General Directorate of Military Factories, known as FM. FM was Argentina's first state-owned heavy industry, born of the vision of General Manuel Savio, who saw Argentina's industrial incapacity as a grave weakness that the army could greatly reduce. The Great Depression cut Argentina off from its traditional source of capital imports, Great Britain. The Second World War confirmed that the British would no longer be in a position to supply Argentine needs for arms or capital investments. This development could lead to disastrous consequences if Argentina were drawn into the war, especially since the Government's pro-Axis sympathies led the United States to embargo arms shipments to Argentina while generously supplying archrival Brazil.

Although free-market conservatives controlled the Congress, by 1941 Argentina's disquieting isolation earned their consent to the creation of FM. The law creating FM called for research and development of Argentine industrial and mineral capabilities to ensure the ability to mobilize industry onto a wartime footing. Once established, Argentina's newly developed strategic industries would be divested to the private sector.

Somehow expansion, not divestiture, became the norm. For all their talk of free enterprise, the military governments after Perón had little desire to reduce their own economic influence by giving away FM installations. Philosophically, officers felt more at home with the statist solution; vital tasks should be left to the government on national security grounds. This began in the military sphere, with arms factories, but in time it spread throughout the economy, sometimes on the flimsiest grounds. "Telephones. Yes. Lines of communication. Better let the army have a hand in the National Telephone Company." And so on. The boards of directors of state enterprises provided an excellent source of retirement income for ex-officers.

Vested military interests in continued state ownership became an enormous obstacle to privatization plans. Even Martínez de Hoz, the great free marketeer, could not cajole (let alone force) the military to surrender to the free market. "We couldn't privatize," complained one former economics ministry official from the Process. "As they say, the army has everything on the ground, the navy everything in the water, the air force everything in the air." Civilian governments generally lacked the free market instinct, as well as the political clout, to attack this bastion of military privilege.

So military enterprises grew and grew. By the 1980s, they employed over 40,000 and billed some $1.5 billion in sales annually. In its strong years, FM comprised 5 percent of gross domestic product. It operated fourteen military factories directly, producing weaponry, explosives, chemicals, steel, electrical conductors. It maintained a hammerlock on the mining sector. But FM's direct activities tell only a part of the story; it also holds large shareholdings in other companies and mixed state-private enterprises, especially in the fields of steel and petrochemicals production. That included 99.9 percent of the shares of Somisa, Argentina's largest steel company.

FM progressed far beyond Savio's wildest dreams, perhaps beyond his wildest fears. Its mandate grew apace with its scale. In addition to supplying for war, FM became charged with the task of stimulating industrial development in low profit or long lead-time industries. FM historians cite Robert McNamara to justify this approach; the former secretary of defense had said that "security is development and without development there can be no security." So FM expansion into the private sector helped prepare military factories for quick wartime mobilization, by keeping them fully-occupied producing consumer goods in peacetime. With this strained logic, FM became a producer of armchairs, subway cars, hunting arms, and ammunition. Seventy percent of total sales went to the private sector; 98 percent of the receipts of the giant Zapla steel furnaces in Jujuy Province came from the private sector.

Through their own companies and influence over other state enterprises, the armed forces squatly occupied an important segment of the internal market. This afforded enormous influence over Argentine economics and politics. Through this complex, the military controlled budgets and jobs; it could favor some concerns by investing in them and squeeze out others by competing with them. Its weight in the corridors of political power gave it a leg up in getting a hold of government funds. Since the state contributed half of the national total in fixed capital investment, it became prudent in private companies to appoint a well-connected, retired officer to the board of directors. The military companies themselves also directed substantial revenues to the armed forces.

Inevitably, military production ran up the diseconomics of scale typical of unwieldy state enterprises. Until 1980, FM received substantial government subsidies and tax breaks. This favoritism encouraged inefficiency in FM enterprises, while stacking the deck against private enterprises who could not successfully enter the market due to the monopoly competition. According to National Deputy Alvaro Alsogaray, FM poured "hundreds of millions of dollars" into Hipasam S.A. to mine iron ore in northern Patagonia, an investment "that will never produce any benefit." Duplication of effort is the rule; the army and the navy each produce their own gunpowder, as well as a host of other products.

Not surprisingly, over the years the Argentina military has become an economic powerhouse, in land, labor, and capital. The army is one of the biggest landowners in Argentina. By 1983, there were 153,000 soldiers in uniform, and military spending comprised 12 percent of the national budget. Each branch of the armed forces owns or controls a domain of large state enterprises. The air force writ runs to aircraft production, the national airlines, air insurance, and travel agencies. The navy presides over a complex including a merchant fleet, shipyards, weapons research and production.

The army has the big kid on the block, drily denominated the General Directorate of Military Factories, known as FM. FM was Argentina's first state-owned heavy industry, born of the vision of General Manuel Savio, who saw Argentina's industrial incapacity as a grave weakness that the army could greatly reduce. The Great Depression cut Argentina off from its traditional source of capital imports, Great Britain. The Second World War confirmed that the British would no longer be in a position to supply Argentine needs for arms or capital investments. This development could lead to disastrous consequences if Argentina were drawn into the war, especially since the Government's pro-Axis sympathies led the United States to embargo arms shipments to Argentina while generously supplying archrival Brazil.

Although free-market conservatives controlled the Congress, by 1941 Argentina's disquieting isolation earned their consent to the creation of FM. The law creating FM called for research and development of Argentine industrial and mineral capabilities to ensure the ability to mobilize industry onto a wartime footing. Once established, Argentina's newly developed strategic industries would be divested to the private sector.

|

| Location of FM factories & establishments |

Somehow expansion, not divestiture, became the norm. For all their talk of free enterprise, the military governments after Perón had little desire to reduce their own economic influence by giving away FM installations. Philosophically, officers felt more at home with the statist solution; vital tasks should be left to the government on national security grounds. This began in the military sphere, with arms factories, but in time it spread throughout the economy, sometimes on the flimsiest grounds. "Telephones. Yes. Lines of communication. Better let the army have a hand in the National Telephone Company." And so on. The boards of directors of state enterprises provided an excellent source of retirement income for ex-officers.

Vested military interests in continued state ownership became an enormous obstacle to privatization plans. Even Martínez de Hoz, the great free marketeer, could not cajole (let alone force) the military to surrender to the free market. "We couldn't privatize," complained one former economics ministry official from the Process. "As they say, the army has everything on the ground, the navy everything in the water, the air force everything in the air." Civilian governments generally lacked the free market instinct, as well as the political clout, to attack this bastion of military privilege.

So military enterprises grew and grew. By the 1980s, they employed over 40,000 and billed some $1.5 billion in sales annually. In its strong years, FM comprised 5 percent of gross domestic product. It operated fourteen military factories directly, producing weaponry, explosives, chemicals, steel, electrical conductors. It maintained a hammerlock on the mining sector. But FM's direct activities tell only a part of the story; it also holds large shareholdings in other companies and mixed state-private enterprises, especially in the fields of steel and petrochemicals production. That included 99.9 percent of the shares of Somisa, Argentina's largest steel company.

FM progressed far beyond Savio's wildest dreams, perhaps beyond his wildest fears. Its mandate grew apace with its scale. In addition to supplying for war, FM became charged with the task of stimulating industrial development in low profit or long lead-time industries. FM historians cite Robert McNamara to justify this approach; the former secretary of defense had said that "security is development and without development there can be no security." So FM expansion into the private sector helped prepare military factories for quick wartime mobilization, by keeping them fully-occupied producing consumer goods in peacetime. With this strained logic, FM became a producer of armchairs, subway cars, hunting arms, and ammunition. Seventy percent of total sales went to the private sector; 98 percent of the receipts of the giant Zapla steel furnaces in Jujuy Province came from the private sector.

Through their own companies and influence over other state enterprises, the armed forces squatly occupied an important segment of the internal market. This afforded enormous influence over Argentine economics and politics. Through this complex, the military controlled budgets and jobs; it could favor some concerns by investing in them and squeeze out others by competing with them. Its weight in the corridors of political power gave it a leg up in getting a hold of government funds. Since the state contributed half of the national total in fixed capital investment, it became prudent in private companies to appoint a well-connected, retired officer to the board of directors. The military companies themselves also directed substantial revenues to the armed forces.

Inevitably, military production ran up the diseconomics of scale typical of unwieldy state enterprises. Until 1980, FM received substantial government subsidies and tax breaks. This favoritism encouraged inefficiency in FM enterprises, while stacking the deck against private enterprises who could not successfully enter the market due to the monopoly competition. According to National Deputy Alvaro Alsogaray, FM poured "hundreds of millions of dollars" into Hipasam S.A. to mine iron ore in northern Patagonia, an investment "that will never produce any benefit." Duplication of effort is the rule; the army and the navy each produce their own gunpowder, as well as a host of other products.

|

| Vigilance & Air Control Radar Project |

Friday, May 20, 2011

democracy in Argentina

[excerpts from Daniel Poneman's Argentina: Democracy on Trial, Paragon, 1987]

In Argentina, the best way to maintain popularity is to stay out of government. It is far easier to score points either by criticizing the incumbent's shortcomings or simply by avoiding the inevitable taint governments suffer when they try to manage a society polarized into powerful competing interests. The Argentines are notoriously impatient, even amnesiac, when it comes to politics. Government popularity quickly erodes . . .

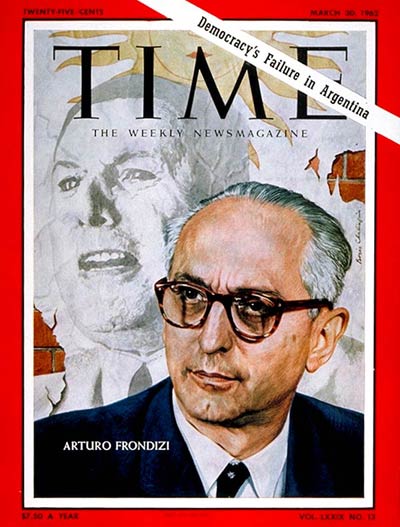

Coups in Argentina have always emerged from a murky amalgam of dissatisfaction and conspiracy, but the 28 June 1966 overthrow of President Arturo Illia is the least explicable of all. Illia was neither engaged in the senile abuse of power, like Yrigoyen, nor intent on subjugating Argentina to his personality, like Perón. He was not poised to impose a successor by electoral fraud, like Castillo in 1943, nor had his party just been defeated by the Peronists, like Frondizi's in 1962. Chaos and terror did not grip the country, as in 1976. Economic growth averaged 9.7 percent per year in 1964 and 1965. Yes, there were problems: an annual inflation rate of over 20 percent (a rate that would later appear rather quaint) and an organized "battle plan" of strikes and factory occupations. But here was no subversion, no rampant corruption, no perilous threat to the fatherland or its constitutional order. The nation's problems were not those that beg for military solutions at the sacrifice of constitutional norms. For these reasons the military takeover of 1966 is sometimes called the frivolous coup. . . .

It is now convenient to forget how enthusiastically the people welcomed the military when it took over in March 1976. Official ineptitude, an insidious terrorism from both right and left, and rampant inflation left the government of Isabel Perón with few friends. Some political party leaders, including longtime Radical Ricardo Balbín, half-heartedly entered last minute negotiations to try to form a multiparty coalition that could save civilian rule. But it was too late. Order had to be restored; the military seemed the natural candidate for the job. The faded scruples against military intervention in civilian politics seemed trivial in that dire hour. The coup brought a collective sign of relief, and was supported by such notable civilians as former president Arturo Frondizi and newspaper editor Jacobo Timerman.

. . . how could constitutional democracy reappear in 1983? By default. Alfonsín's victory was not arduously won against tyrannical force. The armed forces, discredited by the debacles in the Malvinas and the economy, retreated to the barracks and left the government behind them like a spent shell. (The struggle against subversion did not fatally compromise the military's public support; but for its other failures the military might still be in power.) Elections were the only alternative; everything else had failed. Into this political wasteland moved Raúl Alfonsín, seeking the presidency and the vitalization of Argentina's supine democracy.

In Argentina, the best way to maintain popularity is to stay out of government. It is far easier to score points either by criticizing the incumbent's shortcomings or simply by avoiding the inevitable taint governments suffer when they try to manage a society polarized into powerful competing interests. The Argentines are notoriously impatient, even amnesiac, when it comes to politics. Government popularity quickly erodes . . .

|

| Arturo Illia |

Coups in Argentina have always emerged from a murky amalgam of dissatisfaction and conspiracy, but the 28 June 1966 overthrow of President Arturo Illia is the least explicable of all. Illia was neither engaged in the senile abuse of power, like Yrigoyen, nor intent on subjugating Argentina to his personality, like Perón. He was not poised to impose a successor by electoral fraud, like Castillo in 1943, nor had his party just been defeated by the Peronists, like Frondizi's in 1962. Chaos and terror did not grip the country, as in 1976. Economic growth averaged 9.7 percent per year in 1964 and 1965. Yes, there were problems: an annual inflation rate of over 20 percent (a rate that would later appear rather quaint) and an organized "battle plan" of strikes and factory occupations. But here was no subversion, no rampant corruption, no perilous threat to the fatherland or its constitutional order. The nation's problems were not those that beg for military solutions at the sacrifice of constitutional norms. For these reasons the military takeover of 1966 is sometimes called the frivolous coup. . . .

It is now convenient to forget how enthusiastically the people welcomed the military when it took over in March 1976. Official ineptitude, an insidious terrorism from both right and left, and rampant inflation left the government of Isabel Perón with few friends. Some political party leaders, including longtime Radical Ricardo Balbín, half-heartedly entered last minute negotiations to try to form a multiparty coalition that could save civilian rule. But it was too late. Order had to be restored; the military seemed the natural candidate for the job. The faded scruples against military intervention in civilian politics seemed trivial in that dire hour. The coup brought a collective sign of relief, and was supported by such notable civilians as former president Arturo Frondizi and newspaper editor Jacobo Timerman.

|

| Raúl Alfonsín |

. . . how could constitutional democracy reappear in 1983? By default. Alfonsín's victory was not arduously won against tyrannical force. The armed forces, discredited by the debacles in the Malvinas and the economy, retreated to the barracks and left the government behind them like a spent shell. (The struggle against subversion did not fatally compromise the military's public support; but for its other failures the military might still be in power.) Elections were the only alternative; everything else had failed. Into this political wasteland moved Raúl Alfonsín, seeking the presidency and the vitalization of Argentina's supine democracy.

Wednesday, May 18, 2011

things you might not know about Argentina

[tidbits from Suzanne Jill Levine's biography of Manuel Puig: Manuel Puig and the Spider Woman, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000]

The saying goes: The Mexicans descended from the Aztecs, the Peruvians from the Incas, and the Argentines from the boat. At the turn of the [20th] century, over 70 percent of Argentina's population was composed of first-generation immigrants, including "Russians" and "Turks" but mostly Spaniards and Italians.

in 1946 . . . the first (non-British) cars with left-sided steering wheels arrived

[In the middle decades of the 20th century] Latin America constituted a large percentage of Hollywood's foreign audience. Hollywood had, in some ways, more impact in Latin America than at home because it presented both "the real world" (New York, Chicago, London, Paris) and a romanticized paradise, a comforting universe of familiar faces. . . . Hollywood had adopted Mexico, the Caribbean, and South America as an exotic other world, a place of tropical exuberance, romance, sin, and decadence. . . . The film industry in Argentina, more developed than in other Latin American countries except for Mexico, made every effort not only to market these Hollywood melodramas but to reproduce them. . . . Before she became Evita Perón, Eva Duarte was a second-rate actress who attempted to imitate, first for radio soap operas, heroic roles immortalized by the likes of Norma Shearer . . . or Vivien Leigh.

Most Hollywood movies were embargoed in Argentina under Perón's policies to promote national industries

Nina [sic; aka Niní] Marshall, a gifted radio comedienne during the late thirties and forties . . . mimicked to perfection the foibles and, especially, the inflections of Argentine women, inventing a pantheon of characters ranging across the social strata. Most famous for her strident lower-middle-class Catita, Marshall was possible the first popular media artist to make the Argentines laugh at themselves.

Perón's . . . fatal error in Argentina was his anticlerical attitude. Both he and Evita had suffered the humiliation of illegitimate births. Perón took his revenge by instituting reforms in the legal organization of the family so as not to favor legitimate over extramarital offspring, but his ultimate slap in the face to the Church was to authorize remarriage by divorcées.

Argentina, in hard economic times, would always fall back on its feudal Spanish past: The cursi pretensions of an insecure, never-quite-Europeanized middle class, the machismo inherited from Mediterranean grandfathers and fostered by the harsh life of the pampas, and the colonial overlay of British decorum produced a stifling society, one that valued elegant facades and proper appearances more than civil liberties. Up until the late forties and even fifties, when Perón's shirtless workers movement marked a new populist era, men were obliged by law to wear jackets in public places, and could be fined if they appeared in their shirtsleeves.

La Boca, the traditional southside barrio [of Buenos Aires] on the western bank of the mouth of the river . . . was the barrio of sin, where the tango had originated as an obscene sexual rite which only guapos, tough guys, could dance in public; a barrio of compadres, or gangsters, Italian pederasts and prostitutes, putos and putas from all over Europe, often Polish or Jewish, but also always associated with Italian gangsters . . . the ships entering and leaving port, the bustle of people, the colorful tenements with clothes hanging out the windows, the gulls screaming, the flea market in San Telmo, vendors hawking their wares, the old cobblestoned streets and dark winding staircases, the noises of ship horns and buses, the foul smells of the big muddy river.

The saying goes: The Mexicans descended from the Aztecs, the Peruvians from the Incas, and the Argentines from the boat. At the turn of the [20th] century, over 70 percent of Argentina's population was composed of first-generation immigrants, including "Russians" and "Turks" but mostly Spaniards and Italians.

in 1946 . . . the first (non-British) cars with left-sided steering wheels arrived

[In the middle decades of the 20th century] Latin America constituted a large percentage of Hollywood's foreign audience. Hollywood had, in some ways, more impact in Latin America than at home because it presented both "the real world" (New York, Chicago, London, Paris) and a romanticized paradise, a comforting universe of familiar faces. . . . Hollywood had adopted Mexico, the Caribbean, and South America as an exotic other world, a place of tropical exuberance, romance, sin, and decadence. . . . The film industry in Argentina, more developed than in other Latin American countries except for Mexico, made every effort not only to market these Hollywood melodramas but to reproduce them. . . . Before she became Evita Perón, Eva Duarte was a second-rate actress who attempted to imitate, first for radio soap operas, heroic roles immortalized by the likes of Norma Shearer . . . or Vivien Leigh.

Most Hollywood movies were embargoed in Argentina under Perón's policies to promote national industries

|

| radio comedienne Niní Marshall as Catita |

Perón's . . . fatal error in Argentina was his anticlerical attitude. Both he and Evita had suffered the humiliation of illegitimate births. Perón took his revenge by instituting reforms in the legal organization of the family so as not to favor legitimate over extramarital offspring, but his ultimate slap in the face to the Church was to authorize remarriage by divorcées.

Argentina, in hard economic times, would always fall back on its feudal Spanish past: The cursi pretensions of an insecure, never-quite-Europeanized middle class, the machismo inherited from Mediterranean grandfathers and fostered by the harsh life of the pampas, and the colonial overlay of British decorum produced a stifling society, one that valued elegant facades and proper appearances more than civil liberties. Up until the late forties and even fifties, when Perón's shirtless workers movement marked a new populist era, men were obliged by law to wear jackets in public places, and could be fined if they appeared in their shirtsleeves.

|

| La Boca, southside barrio of Buenos Aires |

La Boca, the traditional southside barrio [of Buenos Aires] on the western bank of the mouth of the river . . . was the barrio of sin, where the tango had originated as an obscene sexual rite which only guapos, tough guys, could dance in public; a barrio of compadres, or gangsters, Italian pederasts and prostitutes, putos and putas from all over Europe, often Polish or Jewish, but also always associated with Italian gangsters . . . the ships entering and leaving port, the bustle of people, the colorful tenements with clothes hanging out the windows, the gulls screaming, the flea market in San Telmo, vendors hawking their wares, the old cobblestoned streets and dark winding staircases, the noises of ship horns and buses, the foul smells of the big muddy river.

Tuesday, April 19, 2011

the Chinese discovery of America

[from Gavin Menzies's 1421: The Year China Discovered America, Harper, 2002]

Professor Charles Aylmer, the librarian of the East Asian Collection at Cambridge University in England, informed me of a unique book, I Yü Thu Chih – 'The Illustrated Record of Strange Countries' – a compilation of the people and places known to the Chinese in 1430. The book's cover page is missing so the author is not known for certain, but it is believed to have been written by the Ming prince Ning Xian Wang (Zhu Quan) and printed within a year or so of 1430. It formed part of the magnificent collection donated to the University of Cambridge in the late nineteenth century by Professor Wade, who had spent most of his life in China and was the first professor of Chinese at Cambridge. The Cambridge copy is the only one in existence, anywhere in the world. It has never been translated and only one photocopy has ever been taken, by the Chinese Embassy in London. Professor Aylmer and other learned sinologists are absolutely convinced of the provenance and authenticity of the book.